1Welcome to the second issue of RIDE Digital Text Collections (DTC), which is published as Issue 8 in the RIDE series. We have been working on this issue since last summer. After the initial major interest in reviewing DTCs which lead to the publication of ten reviews in the first issue, we now return to the usual rhythm of publication for RIDE issues, presenting five new reviews.

2As always, this issue is based on the methodological framework of RIDE. Firstly, the reviewers were asked to consider the key aspects of the catalogue of Criteria for Reviewing Digital Text Collections when discussing the respective resource. Secondly, each contribution is subjected to a peer reviewing process and finally, each review is supplemented by a factsheet resulting from a questionnaire. Some statistics resulting from the questionnaires of all reviews on digital text collections so far can be consulted here.

Contents

3The current issue contains four reviews in English and one in German, which are devoted to DTCs originating from different contexts. Two of the reviews discuss textual resources which are of great importance for the study of Classical Antiquity: Perseus Digital Library, reviewed by Sarah Lang, and PHI Latin Texts, by Dániel Kozák. Another two reviews in this issue are devoted to DTCs which are characterised above all by their dedication to a specific literary genre: Anemoskala, a collection of texts of and a concordance tool for Modern Greek poetry, reviewed by Anna-Maria Sichani, and Théâtre Classique, a collection of French-language dramas from the Classical Age and Enlightenment, reviewed by Christof Schöch. Finally, this issue also contains a review that does not primarily originate from the scholarly context, although it is widely used in it: Wikisource, precisely: the Wikisource subcollection of texts in German language, reviewed by Susanne Haaf. What is special about this collection when compared to the other resources reviewed in this issue is that it does not have a clearly defined scholarly editorial team behind it, but rather a group of volunteers, often laymen.

4In the editorial of the last issue, we focused mainly on questions of the classification of DTCs from a terminological point of view, providing a working terminology to further systematize types of DTCs (see the previous editorial). It became clear, however, that the self-designation of resources does not necessarily have to correspond to the type chosen by the reviewers.

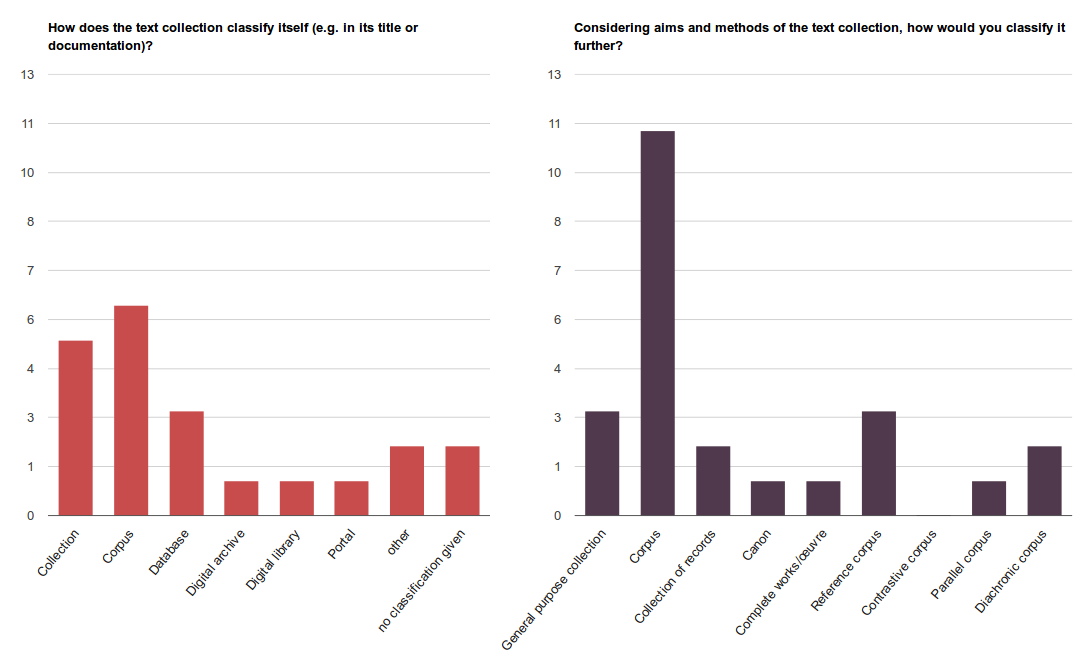

5Fig. 1 shows an updated version of the comparison between the self-classification of the projects as given in their titles and documentation on the one hand, and the classification of the DTCs by the reviewers, on the other hand.1 The charts include all the data gathered for DTCs in the 15 reviews so far. As before, the concept of corpus is used more often by the reviewers than in the self-designation of the resources (11 times vs. 6).2 It has to be emphasized here that the taxonomy proposed by us focuses on aspects of the selection of materials and design of the DTCs in terms of content and research aims (e.g. to provide a loosely structured general-purpose text collection vs. a parallel corpus aiming at the comparison of specific groups of texts). The self-designation, on the other hand, also tends to refer to the aspects of storage, organisation, and presentation of the materials (digital archive, digital library, portal, database).

6There is still a long way to go before sharp definitions of what constitutes which kind of text collection can be provided. However, the primary objective of our proposal is not to set terminological boundaries. Instead, we would like to raise awareness for terminological questions and promote a discourse that sets out the whole range of possible types of DTCs, based on the observations gained from the reviews. In the following, three aspects are discussed that came up during the editing of this issue and which we consider to be particularly important for the consideration and evaluation of DTCs.

On scholarliness

7When considering different types of DTCs, the issue of scholarliness becomes relevant, too. While the Criteria for Reviewing Scholarly Digital Editions include the difference between scholarly and non-scholarly editions as a component in the very definition of the digital edition, we consciously avoided a clear distinction of scholarly and non-scholarly text collections in the Criteria for Reviewing Digital Text Collections. We did so because there are many general-purpose text collections out there which have not been created in an academic context aiming to meet scholarly standards, but which are nonetheless used in scholarly undertakings. This is true, for example, for the Wikisource collection reviewed in this issue. Again, in the case of Théâtre Classique, the question is to what extent the collected texts can be considered scholarly texts. Once reviewed, general-purpose collections and especially larger DTCs see themselves exposed to questions of textual quality and the reviewers are challenged to discuss their understanding of scholarly standards.

8In her review, Haaf cites a statement reflecting the self-conception of Wikisource: “Wikisource versteht sich als wissenschaftlich fundiertes Qualitätsprojekt, das sich möglichst hohen Standards bei der Textwiedergabe verpflichtet sieht.”3 In the discussion, she then focuses particularly on the limits of Wikisource’s claim to scholarliness, but also stresses the value of the resource for scholarly purposes. In a similar vein, Schöch observes about Théâtre Classique: “It is unclear whether any formal quality assurance of the transcriptions, annotations, and metadata has been or is being performed” and later on concludes “this is certainly no scholarly text edition, but could rather be described as a text collection for scholarly use”.4

9It becomes clear that various factors influence the perception and evaluation of the scholarliness of a DTC: the institutional, organizational, and personal background, transparency in terms of text establishment (Where do the texts come from? According to which criteria have they been selected? How have they been treated?), the presence or absence of reports of quality control, but also factors such as the size of a DTC. While there are already well-known standards for text treatment in digital scholarly editions (DSE), no such standards have yet been established for large DTCs which are, amongst other things, used for quantitative text analysis and which necessarily have to draw on a different set of quality criteria than a focused scholarly edition. It is thus not coincidental that both mentioned reviews refer to the DSE when discussing the scholarliness of a DTC. There is obviously a need for more discussion of aspects of quality assurance and scholarly standards for DTCs.

On access and provision

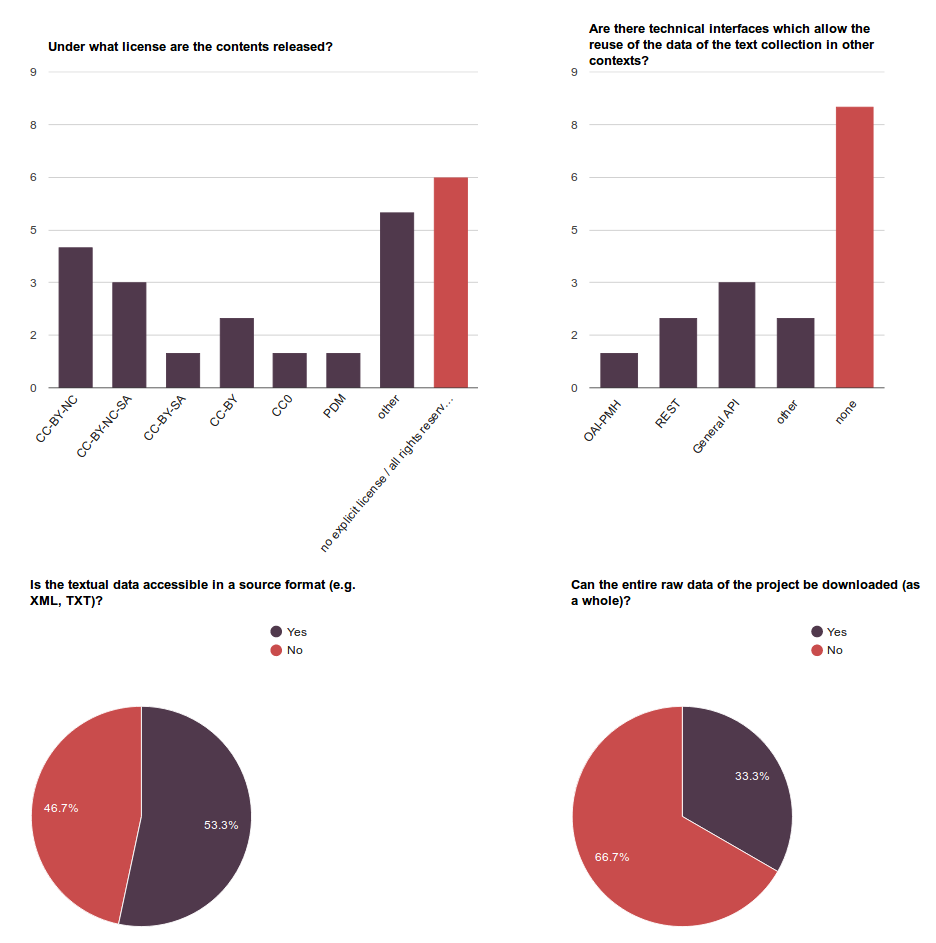

10Another aspect of DTCs that we regard as in need of discussion is the disproportion of online accessible DTCs and the lack of possibilities to harvest the data from these resources. The accessibility and provision of the data is discussed in some of our reviews and can be also observed in our statistics. Fig. 2 shows the results of the questionnaire for the following four questions related to access to the texts:

- Under what license are the contents released?

- Is the textual data accessible in a source format (e.g. XML,TXT)?

- Are there technical interfaces which allow the reuse of the data of the text collection in other contexts?

- Can the entire raw data of the project be downloaded (as a whole)?

11There is a general tendency towards an “open policy” for providing textual resources via a user web interface and to allow reuse of the texts in principle by setting appropriate licenses. For almost two-thirds of the projects, the reviewers indicated licenses that allow further reuse. However, this trend to “openness” is not reflected to the same extent in the availability of overall download options and technical interfaces which would facilitate the reuse of the texts on a large scale. According to our statistics, only slightly more than half of the DTCs provide their textual resources in a reusable source format (7 out of 15), and even less DTCs (one third) offer their data for downloading. For almost half of the reviewed DTCs, the reviewers indicated the existence of an API.5

12Our statistics do not show a drastic picture in this sense, as many creators of DTCs seem to be aware that the data can be used in other contexts and decide to offer them accordingly. On the other hand, however, it is disappointing that many projects still seem not to prioritize the free availability of their data, leaving many high-quality textual data “locked up” in the respective resource. Sichani describes this contradictory situation of access to the contents as “‘read-only’ or ‘see-but-not-touch’ mode”.6 In her review on Anemoskala she suggests that “text collections should not be seen as the end-product or an end in itself but as the starting point for sophisticated computational processing activities” and pleads to give access to the source data in order to “move beyond ‘screen essentialism’”.

On long-standing projects

13The last aspect we want to discuss is the challenge of reviewing DTCs with a long history, such as PHI Latin Texts or Perseus Digital Library. Both are, so to speak, “dinosaurs” of DTCs. Perseus has been developed online since the 1980s and is still being developed further, in close connection with other classical resources in the WWW. PHI Latin Texts appeared on CD-ROM since the early 1990s and is online available since 2011. It is apparently no longer being continued.

14In general, there is more heterogeneity and inconsistency to be expected from long-standing DTCs. The state of the texts included may be non-uniform when they have been prepared in different phases. Indeed, Lang declares in her review, that “every generation of Perseus texts followed a different paradigm of production”.7 It is likewise possible that the methods used stem from an earlier period and do not necessarily reflect the state of the art in creating DTCs. A review needs to take into account the historicity of the resource and the context in which it has emerged. For instance, Kozák notes in his review on PHI Latin Texts, that the DTC “is not based on up-to-date standards for the digital encoding, access, and presentation of textual data”. However, he emphasises at the same time that it “has proven to be in practice a wonderful tool […], widely used by classical philologists for decades now”.8 Finally, also the relation of the reviewed DTC to other resources must be considered. Side projects may have emerged from historical core projects, or they may have been absorbed in a bigger project.

15The above-mentioned aspects of long-standing projects require a particularly differentiated consideration and some aspects can only be examined briefly within a single review (e.g. the relation to other resources). However, it should be emphasised that long-standing DTCs are at the same time of particular interest for reviewing, precisely because of their history. In a way they document the development the Digital Humanities have undergone in the last decades. Lang attests Perseus in her synopsis a value that goes beyond the actual contents of the DTC: “The project has had a great methodological impact on the discussion of best practises for the Digital Humanities and has been a pioneer of the field.”9

***

16The publication of this issue, like the previous one, has once again demonstrated how diverse textual resources in the World Wide Web are, be it with regard to their creation, scholarly enrichment, provision, or distribution. The particularities of the resources hold challenges when discussing them.10 Together with us, the reviewers of this issue have embraced the challenges of reviewing DTCs with great enthusiasm. We want to thank everyone involved in the creation of this issue and hope you enjoy reading it.

17The editors, Frederike Neuber and Ulrike Henny-Krahmer, February 2018.

Notes

1. As before, multiple options could be chosen, as well as “other” in cases where none of the proposed options was considered adequate.

2. According to the last issue, the definition of corpus is: “a collection of texts that has been created according to some selection criteria (language, author, country, epoch, genre, topic, style, etc.) which makes it more specific than a general-purpose collection; not necessarily aiming at completeness or representativeness; e.g. the ‘Corpus of English Religious Prose’, ‘Letters of 1916’, ‘Corpus of Literary Modernism’.”

3. “Wikisource sees itself as a scholarly grounded project which is bound to high standards of text reproduction as much as possible” (translated by the editors), see Haaf, Susanne. 2018. “Rezension der Deutschsprachigen Wikisource.” RIDE 8, § 2. doi: 10.18716/ride.a.8.4 https://ride.i-d-e.de/issue-8/wikisource/, accessed: February 23rd, 2018.

4. Schöch, Christof. 2018. “Review of ‘Théâtre Classique’.” RIDE 8, § 11. doi: 10.18716/ride.a.8.5 https://ride.i-d-e.de/issue-8/theatre-classique/, accessed: February 23, 2018.

5. At this point, our data set is still too small to allow an extrapolation of this disproportion to DTCs in general. However, we will continue to observe the development of the statistics regarding licensing and provision of data in the future.

6. Sichani, Anna-Maria. 2018. “Anemoskala: corpus and concordances for major Modern Greek poets.” RIDE 8, §26 and §27 in the following. doi: 10.18716/ride.a.8.1 https://ride.i-d-e.de/issue-8/anemoskala/, accessed: February 23, 2018.

7. Lang, Sarah. 2018. “Review of ‘Perseus Digital Library’” RIDE 8, § 4 in the following. doi: 10.18716/ride.a.8.3 https://ride.i-d-e.de/issue-8/Perseus, accessed: February 23, 2018.

8. Kozák, Dániel. 2018. “Review of ‘PHI Latin Texts’” RIDE 8, § 17 in the following. doi: 10.18716/ride.a.8.2 https://ride.i-d-e.de/issue-8/phi, accessed: February 23, 2018.

9. Lang § 32, see ftn. 7.

10. At the annual conference of “Digital Humanities in the German speaking countries” (DHd2018) we will discuss some of the difficulties when reviewing digital resources such as text collections and scholarly editions in a dedicated panel: “Alles ist im Fluss. Ressourcen und Rezensionen in den Digital Humanities”, Wednesday, February 28, 2018 (submitted by F. Neuber, U. Henny-Krahmer, P. Sahle and F. Fischer).