Mark Twain’s Letters, 1853–1880, Edgar Marquess Branch, Michael B. Frank, Kenneth M. Sanderson, Harriet Elinor Smith, Richard Bucci, Victor Fischer, Lin Salamo, Sharon K. Goetz (ed.), 1988-2010. http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/search?category=letters;rmode=landing_letters;style=mtp (Last Accessed: 12.01.2018). Reviewed by Elise Hanrahan (Freie Universität Berlin), hanrahan.elise@gmail.com. ||

Abstract:

The Mark Twain Project Online (MTPO) provides digital critical editions of Mark Twain’s writings for the purpose of scholarly study. The edition project creates a foundation for in-depth research on Mark Twain’s person and texts, as well as contributes greatly to this research itself. All the editions and resources from the MTPO are available free of cost and without registration. The goal of the edition is to publish all of Mark Twain’s writings and this review concentrates particularly on their digital edition of Mark Twain’s letters. This edition project achieves a great deal of transparency regarding editorial principles and practices, making it easy for the reader to follow the editorial decisions. The amount of scholarly work put into the editing and commentary is commendable and offers a vast amount of information for research and analysis. The technical aspects of the digital edition are satisfactory, providing for a digital edition that is easy to read and use, however does not reach the same level of excellence as the critical text and commentary. Considering however that the MTPO went online over ten years ago, in 2007, its usability has stood the test of time.

Introduction

I am sorry to ever have to read anybody’s MSS, it is such useless work—the Great Public’s is the only opinion worth having(SLC to Orion Clemens, 15–18 March 18711 )

I was asked to review an online edition of Mark Twain’s letters, about which the Great Public has already spoken, one which has been an ongoing success for the past ten years. Despite this fact, and despite Twain’s stance on individual opinions, I was happy to take on the job of delving into the edited text of the Mark Twain Project Online and examining the website, if only because this edition project is unfinished and has many more years of work ahead of it. It is an ever-growing and evolving effort; thus it is hoped that a review even at this stage may shed new light.

2Samuel Langhorne Clemens(1835-1910), better known as Mark Twain,2 is one of the USA’s most famous authors. His novels The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn are well-known throughout the world and his bold, satiric, and often pithy writings make headlines even today.3 For more than a century, his works have remained entertaining, challenging, and relevant.

3 The Mark Twain Project Online (MTPO) provides digital critical editions of Mark Twain’s writings for the purpose of scholarly study. The edition project creates a foundation for in-depth research on Mark Twain’s person and texts, as well as contributes greatly to this research itself. All the editions and resources from the MTPO are available free of cost and without registration. The project created print editions before going digital in 2007 with the launch of MTPO, and today they continue to publish both online and in print. This review will concentrate on the digital edition of Mark Twain’s letters.4

4The MTPO aims to publish everything that Mark Twain wrote, no small task. On its website Twain’s texts are split into two categories, Letters and Writings. Under the latter category, five critical editions are available, including his most famous works, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, as well as the long-awaited Autobiography of Mark Twain. Under the category Letters there are over 2,600 edited letters and about 30,000 records of letters (metadata). Considering all that Mark Twain wrote5, there still remains much to be edited and published. Under the heading ‘Coming Soon’ one finds the titles Notebooks & Journals, Volumes 1–3 and Early Tales & Sketches, Volumes 1–2.

5The MTPO has already been reviewed multiple times, by The New Criterion, the Times Literary Supplement, and many others.6 The reviews are overwhelmingly positive and print editions published by the Mark Twain Project have received numerous awards;7 additionally, the entire project has the seal of approval from the Modern Language Association. This review will concentrate on the MTPO’s digital collection of Twain’s letters and will focus particularly on the editorial practice and the edition’s characteristics as a digital publication.

6The archival material, originally bequeathed from Mark Twain to his daughter Clara Clemens Samossoud, came to its current home at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1942 and is now part of an archive entitled The Mark Twain Papers, housed at the University’s Bancroft Library. A research team produces the critical editions, which are published by the University of California Press. The first critical print edition was published in 1967, and the first digital edition followed in 2007 with the launch of the MTPO.

7The project has been funded since 1966 primarily by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), a grant for which they must re-apply every two years, as well as by matching private donations and through other public support (including that of the Bancroft Library itself). The MTPO website states that the amount of private donors must grow in order for the project to continue. It should also be noted that President Donald Trump has attempted to eliminate the NEH8 and the MTPO is just one of countless projects that would struggle for survival were such a measure enacted.

8The digital publications have not completely replaced the paper versions, as some of the editions still appear both online and in print. For instance The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was printed first in 2010 in paper form by the project (three years after the MTPO’s inception) and only after this initial print publication was it made available online for the MTPO in 2017. A slightly befuddling aspect of the project is the relationship and differences between the texts online and those in print. It would be helpful if there were a few lines on the website to clarify their correlation. Ideally the connection would be detailed between texts that are a digitized version of editions printed in the past (before MTPO existed), between texts created concurrently for both digital and print publication, and the plan for texts published in the future.

9Most of the above information for this introduction was found on the project’s website.9 Transparency is a key factor that this review will be examining, and easily-accessible project information is an important part of this. The MTPO has clearly made an effort to share details about the project and its history. This review will also examine the transparency of the critical text as well as the digital aspects of the edition. In terms of the critical text this means documentation of the decisions made by the editor, as well as their reasoning behind those decisions. In terms of the digital aspects this means access to encoded texts and an explanation of the technical infrastructure.

10This review, as mentioned above, examines specifically MTPO’s critical edition of Mark Twain’s letters. In the following section some basic information about the digital collection of letters will be given and the relationship between the print and online editions will be examined. Additionally, the Guide to Editorial Practice, which is published on the website as part of the letters edition, will be examined. In order to see the ‘guide’ in action, a letter from the edition will be studied alongside a facsimile of the original. For those researchers not just interested in close readings, but also in more general questions that can be asked of the data, a test search will then be run. Some of the more general resources on the website will be looked at, and finally, there will be comments on the technical aspects of the project.

The Letters, Introduction

11 Under the navigational heading Letters is the main page for the critical edition of Mark Twain’s letters. There one finds multiple avenues by which to begin an exploration of the texts (simple search, advanced search, list by date, list by name, etc.), as well as links to the title page and the Guide to Editorial Practice. There are 2,691 edited letters available and 29,402 letter metadata. There are 2,691 edited letters available and 29,402 letter metadata. Of the edited letters, 98 include a facsimile.10 Each letter has an ID number and is encoded in TEI-XML. The edited letters date from 1853, when Twain was 17 years old and had recently left home, and reach up until year 1880, when he was 45 and a well-established writer and celebrity. The cataloged letters cover a much wider range of dates and persons, and on the website it states that more edited letters will be added.

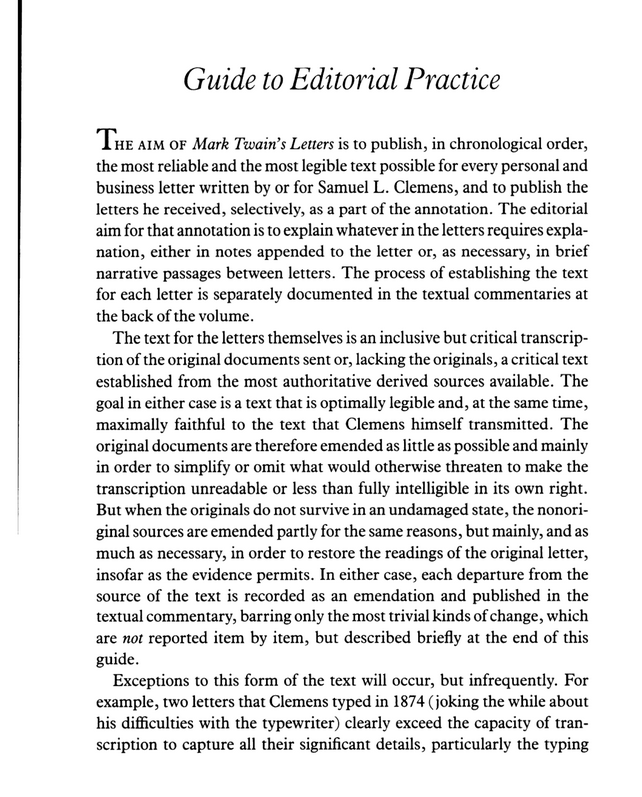

Print and Digital

12Before going digital with the launch of MTPO in 2007, six volumes of Mark Twain’s letters had already been published by the project in print form between 1988 and 2002. These six volumes were transformed into TEI-XML and made available online as part of the MTPO. It can be inferred (although an explicit remark from the editors would be helpful) that the letters and accompanying editorial information found in the digital versions does not differ from the print editions, which are still available for purchase. I compared one letter from the printed edition to its digital counterpart and found this (at least in this random sampling), to be true.11

13In the section on the website titled Recent Changes one sees changes of all kinds made to the website and edition texts. It is a relatively short list: 50 entries spanning a decade, but theoretically one could find here significant alterations to any letters in the digital edition. Here are two examples of the information recorded there:12

- 2009-04-02: Minor corrections to layout (inline salutations) entered for 36 letters, 1853–1880; recipient identified for UCCL 12963

- 2011-05-16: Corrections to annotation entered for five letters, four of which now recognize Frank Fuller’s second wife, Mrs. Annie Fuller: UCCL 02768, 02785, 01041, 01071, 01107 13

14This documentation of changes includes not only alterations made to letters since they were published online but would also by its nature document differences in the digital and print versions. This is, however, based on the assumption that the initial digital publication of the letters contained no significant deviations from the previously printed editions.

15There are also letters on the website that were not previously printed by the project. These are the letters that would have made up a printed seventh volume (Mark Twain’s Letters, 1876–80) as well as a small collection titled Mark Twain’s Letters Newly Published 1. As both of these are only available online, it would appear that, for the letters at least, everything produced after 2007 is published exclusively on the digital platform and is no longer produced in printed volumes.

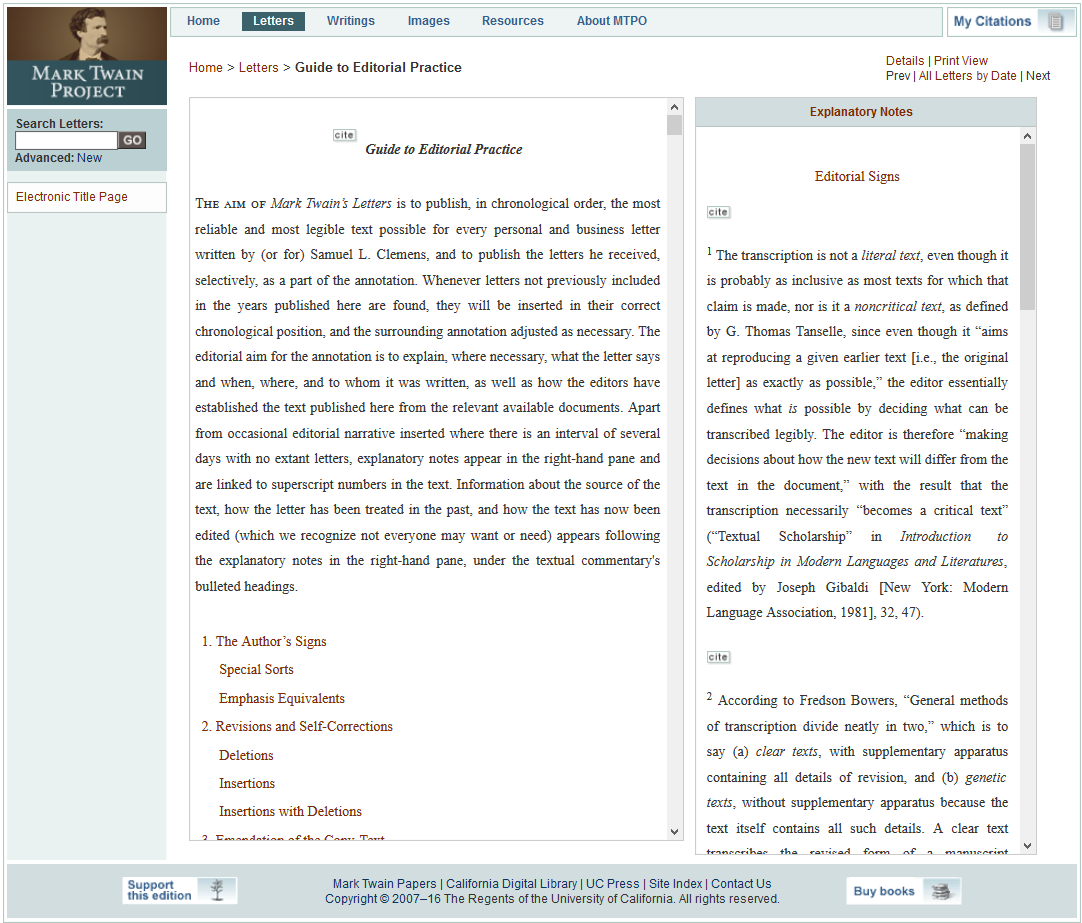

16Interestingly enough, despite originating from different volumes spanning many years, all of the letters on the website are linked to the same title page and to the same Guide to Editorial Practice. This guide will be looked at in detail in the following section. Here it can be noted that it was written by Robert H. Hirst, who is now the general editor of the letters, in 198714, and that he revised it for the MTPO in 2007.

17 I was skeptical as I saw that the editorial guide was altered in 2007 and yet claims to be applicable to all edited letters post-1988. I examined the printed volumes and found that each volume, except volume four (which simply refers to the guide in volume three), includes this Guide to Editorial Practice. When one compares the content of the guide between the printed volumes one sees that there are differences between the volumes, but nothing substantial—the editorial principles do not change. The 2007 version of the guide mentions digital aspects, different editorial symbols used for the online publication, and so forth, but it remains essentially the same as the original guide published in 1988. This can only be possible with extreme consistency in the editorial practice, despite spanning an extensive time period and multiple editors working on the project. Undoubtedly this is partly due to the fact that Hirst has been part of the project since its foundation. In conclusion it seems indeed unproblematic to have one guide, revised in 2007, for all the letters on the website

The Editorial Practice

Fundamentally, the text of any letter is a matter of historical fact, determined for all time by the original act of sending it.(Mark Twain Project Online, Guide to Editorial Practice)

As mentioned above, the Guide to Editorial Practice for Twain’s letters was first written in 1987 by Hirst, and has since been the method used for all of Twain’s letters in the edition project. The editorial practice for the letters is explained herein wonderfully and it offers a commendable amount of transparency. The facts that these guidelines are available to the reader, are well-written, and can be found with ease, earns it much praise. The guide is a pleasure to read—no small feat for a text that describes in detail an edition’s editorial philosophy and its practical implications. Here I will look at some of the principles expounded on within the guide and a few detailed examples of the editorial practice as described therein. As the guide is quite long, only a few aspects will be mentioned. The goal is to gain insight into the editorial principles and how they are explained, allowing an evaluation of both and later a more informed evaluation of the edited text.

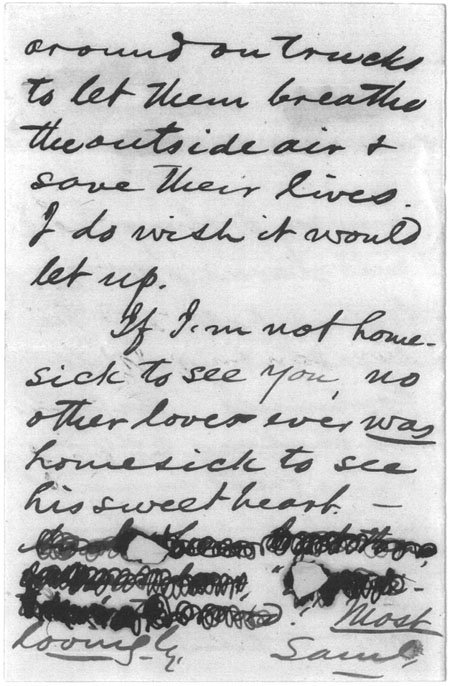

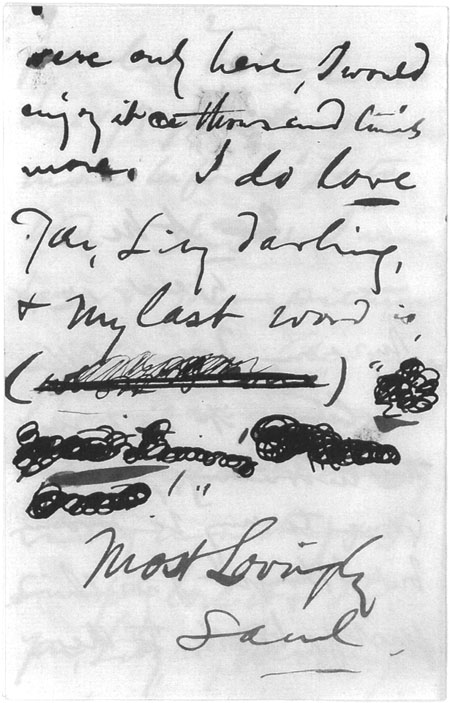

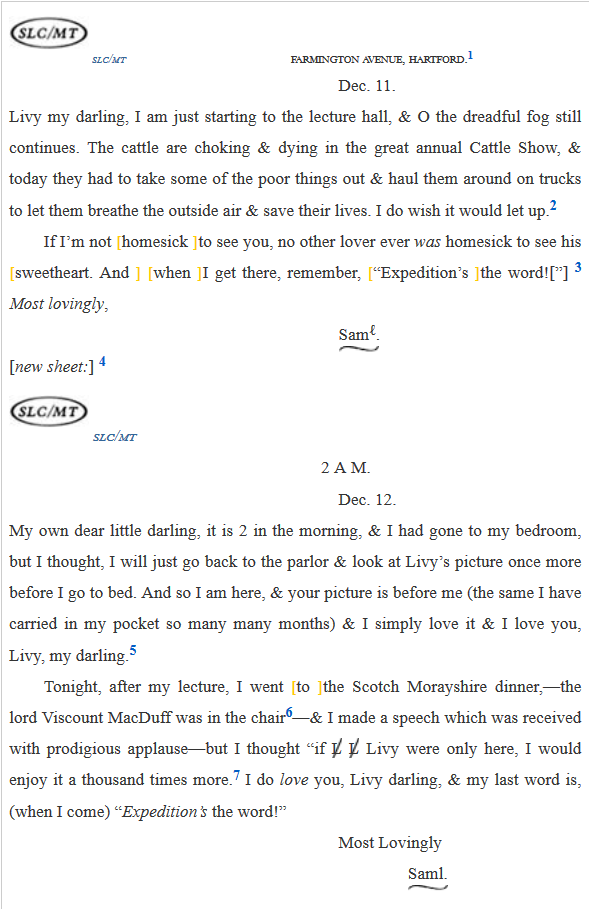

19According to the guide, the editors are providing letters which are extremely faithful (‘maximally faithful’) to the original handwriting. They write, ‘We must begin, in fact, with the assumption that almost any aspect of an original letter might be significant, to either the writer or the recipient, or both—not to mention those for whom the letters are now being published’.15 Thus the editors strive to emend the text only when absolutely necessary for legibility or intelligibility. The editors exclude in the transcription any deletions or revisions that were made after the letter was already sent and received, even if alterations were made by the original writer or recipient. We will see a practical example of this below with the examination of an actual letter.

20The editors call the result of their method, i.e. the edited text, ‘plain text’, a term of their own creation. In doing so they wish to differentiate their result from Fredson Bowers ‘clear texts’ and ‘genetic texts’.16 Clear texts being those for which textual phenomena are described in the apparatus, and genetic texts being those in which textual phenomena are found represented in the text itself, displayed through editorial symbols (such as a diamond for obscured letters, etc.). ‘Plain text’ aims to be a kind of combination of these two methodologies, with some editorial symbols used in the text as well as some information found in the textual apparatus. This approach should serve the editors’ goals of ‘maximum fidelity’ and ‘maximum legibility’. Exact details of how ‘plain text’ achieves this combined aim is not clearly stated, but presumably it is because through the choice of either in-line editorial markings or information being placed in the apparatus, the option can be chosen which is least obtrusive to reading the text (legibility), yet without compromising the information itself (fidelity). This is however my own inference. For more information about this method and result, one is referred in a footnote in the guide to Mark Twain’s Notebooks and Journals. This edition, however, is not available on the website, and exists only in printed form. To this end, a few more salient lines in the online guideline about the theory of ‘plain text’ and how it is created would have been appreciated.

21As it is impossible to transcribe everything from the original handwriting, a key part of the editor’s job is to decide what not to include in the edition. The MTPO editors state:

Like all diplomatic transcription except type facsimile, plain text does not reproduce, simulate, or report the original lineation, pagination, or any other formal aspect of the manuscript, save where the writer intended it to bear meaning […](‘Guide to Editorial Practice, (MTDP 00005).’ In Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2007.)

22Thus it has been decided that most line breaks, minimal differences in indentations, etc., should not be depicted in the transcription. This is reasonable and to be expected of a critical edition and is an important qualification of the earlier quote, which stated that almost any aspect of the original letter might be significant. The ‘almost’ here is expounded upon – there are aspects of the text that the editors deem not to be significant, such as line breaks that occur due to the size of the paper.

23The section of the guide headed Emendation of the Copy-Text includes further insights into the editorial philosophy, as well as itself being an exemplary text showcasing the laudable determination of the editors to be as transparent as possible. This section goes into extensive detail to describe when and for what reasons a letter might be emended by the editor. For instance, when a letter is available only as a newspaper printing (there is no handwritten original), errors are classified by the editors as either originating with the typesetter (thus emended in the edition text) or from Mark Twain himself (thus not emended). It seems as though this distinction could have a large and nebulous gray area that is not mentioned in the guide. Despite this qualm, however, it is certainly true that some errors are without question typographical errors, such as transpostion or incorrect font, of which they give examples. Emendation decisions can often be argued with, but of real importance is whether or not the principles behind the decisions are clearly stated for the reader to understand, and this guide makes every effort to do so.

24The editors explain that, although they in principle do not correct or change Twain’s original text, exceptions are made. Essentially, to be avoided is anything deemed liable to cause further confustion in its transciption. They cite the example of Twain’s unique usage of a dash to justify a line, which we will see below when examining an actual letter. Transcribing this dash does not add any meaning to the transcription but instead would add confusion, especially since the original lineation is not usually reflected in the edited text. It is important to note that such alterations from the editor are not silent emendations, but recorded in the apparatus. Similarly, ambiguities such as hyphenated compound words which are split due to a line break are necessarily emended. The exact line breaks are usually not recreated in the edition text and it is impossible to know if for instance (using the example from the guide) Mark Twain meant waterwheel or water-wheel in such a case as when the word is split due to a line break. The editors summarize this nicely in the following quote, which also nicely represents, in my opinion, their general editorial philosophy:

The question posed by such details is not simply whether including them would make the text more reliable or more complete (it would), but whether they can be intelligibly and consistently included without creating a series of trivial puzzles, destroying legibility, while not adding significantly to information about the writer’s choice of words or ability to spell. There are, in fact, a nearly infinite variety of manuscript occurrences which, if transcribed, would simply present the reader with a puzzle that has no existence in the original.(‘Guide to Editorial Practice, (MTDP 00005).’ In Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2007.)

25In this quote the editors explain once again their loyalty to the concept of maximum fidelity and maximum legibility, and their refusal to create unnecessary puzzles. It is a philosophy that does not forget that in the end the texts are intended to be read, and their job is to facilitate that act. Overall, the guide does an excellent job of sharing the general principles behind the creation of the edition, as well as describing in detail how the text is transcribed and edited, and the reasoning behind those decisions.

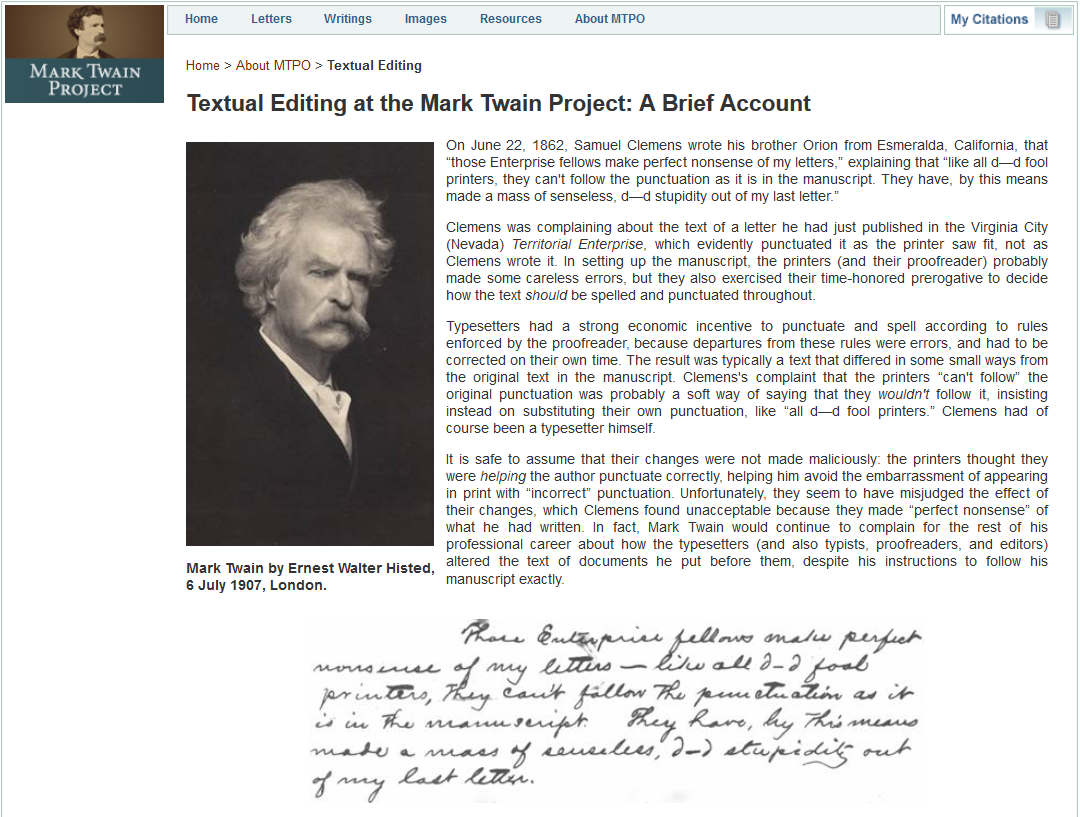

26 In addition to the Guide to Editorial Practice, one also finds on the website a link under About MPTO called Textual Editing at the Mark Twain Project 17. This leads to a text, also from Robert H. Hirst, which is something like an introduction to scholarly editing, using practical examples from Mark Twain texts. It is a fantastic resource to offer on the website. It focuses on the main concepts of editing and does not shy away from addressing difficult questions, such as those pertaining to the nature of a dynamic authoritative text, for which Hirst uses the word ‘unstable’. This is the concept that a particular critical edition is never the last word on the author’s text, but part of a continuing conversation. For instance, one editor could interpret something differently than another editor, or new discoveries could be made which altered a text or even disproved a previous editor’s hypothesis.

27One can also gather in this piece more about the edition’s particular editorial principles. Author intention and the attempt to recreate the original text are at the core of their editorial philosophy. This becomes more relevant for editions of Twain’s published works rather than his letters, but is interesting nonetheless. The slippery nature of author intention is not addressed by Hirst. He does not mention that Twain’s wishes regarding his writing might have changed during his lifetime, perhaps even from one day to the next, let alone the fact that claiming to know any form of author intention can be extremely difficult and must sometimes involve speculation. This philosophy is however typical for the style of editing found in the United States and United Kingdom, based on editing Shakespeare’s plays, which Hirst himself explains.18 However and more importantly, one can safely say that the MTPO critical editions hold up to the standards and principles expounded and presented in this text.

Example Letter

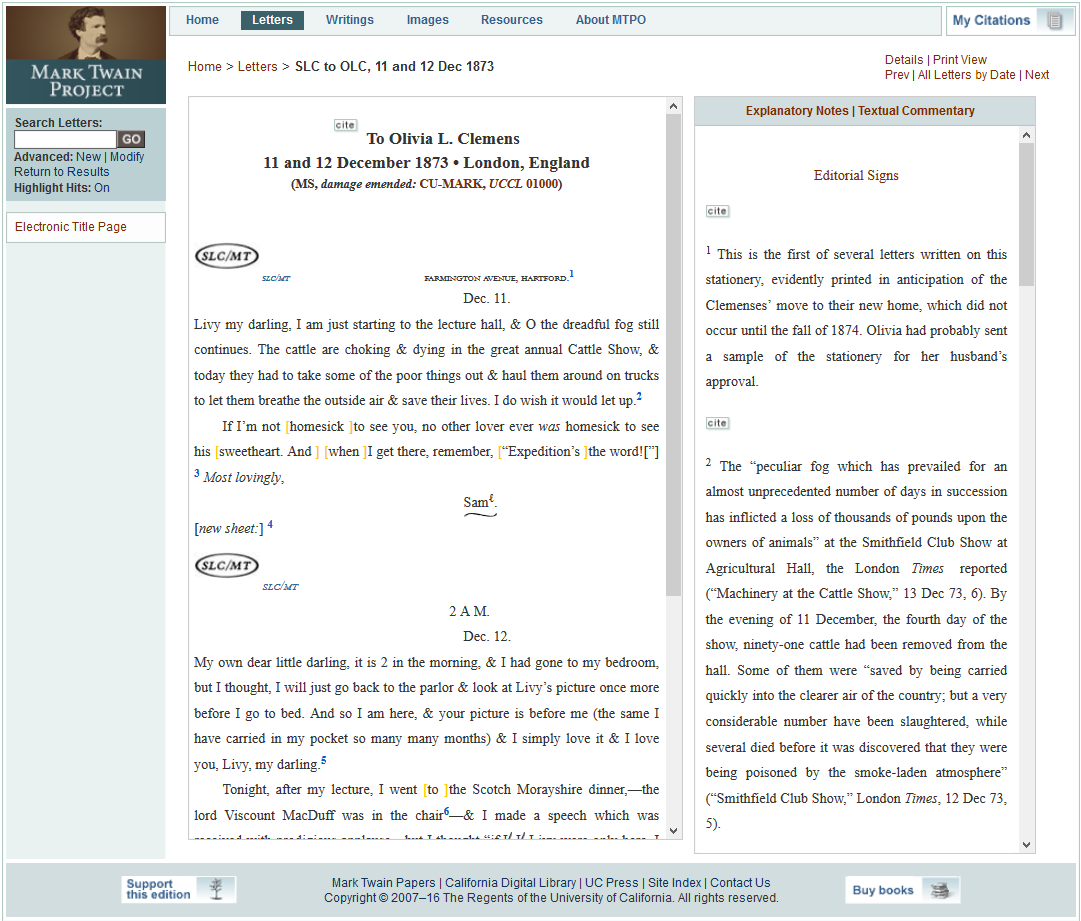

28The example letter used for this review was chosen under the conditions that a facsimile of the original handwriting be available, and that the letter have editorial commentary.19 The letter is from Mark Twain to his wife Olivia, written about three years after their marriage in 1873, while he was away travelling to London, England and she was at their home in Hartford, Connecticut.20 We will look at the transcription of the letter, the editorial commentary, and the usability and readability of the text as a digital publication.

29 The most interesting transcription decision in this letter pertains to the crossed-out lines, on which we will concentrate, as found on pages two and six of the letter (see Fig. 6 and 7). One can see on the facsimile that the last lines on the second page as well as the lines at the end of the letter are heavily cancelled. According to the Guide to Editorial Practice a cancellation should be depicted in the edition’s text with a rule (a horizontal line through the words), but in both of these cases there is no depiction of the crossed out words in the edition text at all. Why not? As explained in the letter’s footnote, the editors think that these lines were crossed out later, after the letter was received by Olivia. Their reasoning for this is, among others, that the ink is of a different color and density as the ink otherwise used in the leter. The editors explain that the manner of the strike seems to be in Twain’s looping style, implying that he probably crossed the words out himself at a later time, after Olivia had already received the letter. The cancellation is not depicted in the edition because according to the editorial practice (as mentioned above) the letters are always transcribed to reflect their state when they were sent. In this case the letter was likely sent without these words crossed out.

30And yet why would Twain cross these words out later (if that is what happened)? The first, not crossed out sentence reads: ‘If I’m not homesick to see you, no other lover ever was homesick to see his sweetheart.’ 21 Followed by the crossed out text: ‘And when I get there, remember, ‘Expedition’s the word![‘]’ 22 At the end of the letter again crossed out is ‘(when I come) Expedition’s the word’23. The editors suggest in the footnote that these words had a special meaning for Mark Twain and Olivia and that they did not want anyone, even in the future, guessing at it.

31The decision to not depict the strike in the edition text remains consistent with the editors’ principles. Whether or not the text was crossed out before or after it was sent is however nearly impossible to establish. The editors base their decision on the change of ink and pen, as well as on the content of the lines. As the editors suggest, the words read as though they may have had an intimate meaning for Mark Twain and Olivia. One can understand that the couple might have wanted to eliminate those lines before filing the letter away in storage, in order to keep it private. This is however obviously a bit of a supposition on the editor’s part, but in the end the editors have to decide one way or another, either for depicting the cancellation or not doing so. The reader may disagree with the conclusions drawn, but such is the process. It is crucial that the reader be able to see that which was omitted in the transcription, as well as the editors’ reasoning behind that decision.

32There are two more small examples of the editorial principles in practice which one can observe here. Firstly, in the original, the word ‘was’ is underlined, and in the edited text ‘was’ is in italics. This is in keeping with their guidelines for depicting emphasis, for which they even have a convenient chart.24 Secondly, Twain’s dash after ‘sweetheart’ is omitted in the transcription (the emendation of which is of course noted in the apparatus). As explained in the Guide to Editorial Practice and mentioned above, this dash falls under the category of his usage of a dash to justify the line, and thus is not transcribed in order to avoid unnecessary confusion.25

33The editorial commentary of this letter (called ‘explanatory notes’ in the edition) is spectacular, and generally when one reads through the letters, one sees that the commentary is one of the aspects which contribute to elevate this edition. The commentary is thorough, helpful, interesting, well-written and could make a fascinating volume in its own right. It is an unfortunate tendency for many digital editions of letters to provide little commentary, or even to include none at all. This is most often due to lack of funding and time; while students or junior editors can transcribe and edit, commentary is often the task of a senior editor and can be an enormous and intimidating job. The amount of research, and the facts thusly uncovered are always many times more than those which actually end up in the edition, and so oftentimes hours – or even days – of work could be invested in the footnote of a single sentence.

34The letters written between 1877 and 1880 (about 600 letters in all) are unfortunately without commentary. It is a small amount compared to the over 2,600 total letters which do include commentary, but they also comprise those most recently published. Hopefully MTPO will continue to prioritize editorial commentary, and it will be added for these letters at a later date.

35 As far as the presentation goes, the letter is easy to read, with the commentary and apparatus in a separate section on the right-hand side. It is possible to jump to the relevant commentary or apparatus entry through links in the edited text. There is a print view as well as a details link which shows how to cite the letter. By no means is it a particularly dynamic edition with lots of linked data and many manipulable viewing options, etc., but it is satisfactory. The design and functions are relatively simple and sleek and all together make for a pleasant reading experience.

Example Search

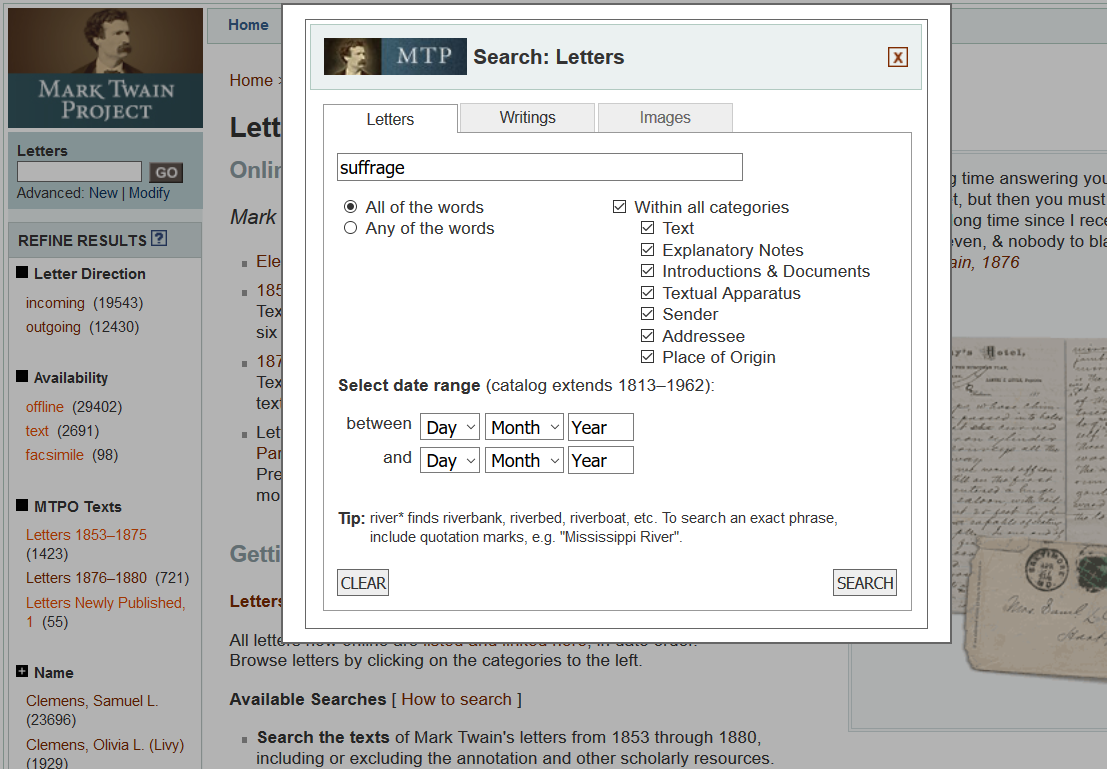

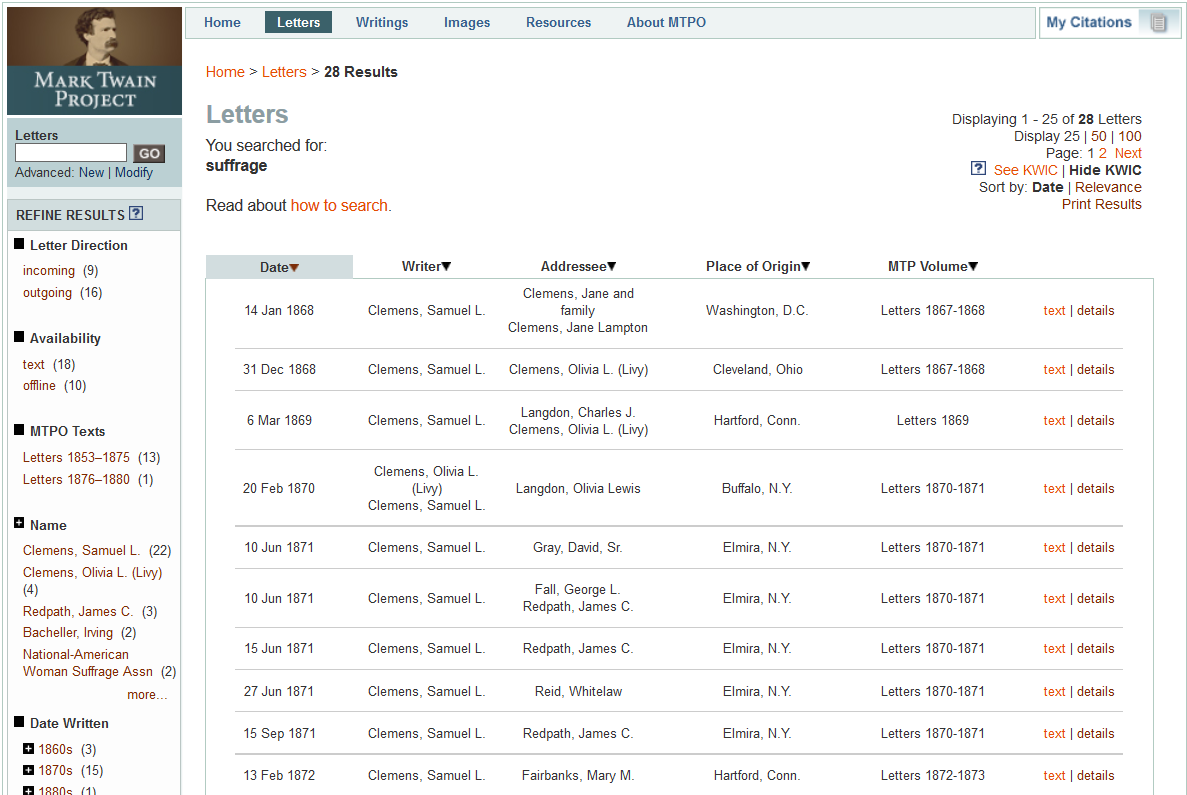

36One can enjoyably browse through the letters as though in a book, but a scholar looking to do research will make use of additional tools on the website, especially the search function. As an example research quest, I will do a little investigating within the letters using the search functions, to see how successfully I can find what I’m looking for. I am interested in learning more about Twain’s stance on women’s suffrage, an important issue during his lifetime, so that’s where I’ll begin my search.

37 Simply searching for ‘suffrage’ in the letters yields 18 results, with a nice overview of the individual letters on the results page. On the left side of the page one can filter the search results (by incoming or outgoing epistles, name, etc.). Through the ‘keyword in context option’ one can, without opening the letter, see the context of the keyword. This is important in my example case, because Twain sometimes wrote of suffrage more generally and not just as it pertained to women.26 Some quite intriguing-looking letters between Twain and diverse suffrage organizations are not yet edited and available, but one can see their metadata. Of the 18 letters, ten were both relevant to my inquiry and had been edited and published, and thus available to read online.

38When looking at the ten letters the commentary is, unsurprisingly, incredibly helpful and offers a much-appreciated springboard for more detailed research. The commentary refers to other letters that are relevant to women’s suffrage, to lectures from Twain, etc., and references to other letters are linked directly so one can easily click on and peruse them. This letter from March 12, 187427 is just one example of such excellent commentary. There was however a small oversight at the end of one comment of this letter. The comment refers to specific pages in volumes four and five of the letters. There is no way to locate such particular pages (most likely additional commentary) on the website. One would have to actually procure the printed letter volumes to find the exact pages, which is neither a practical nor always a feasible option. In a digital edition it would be more appropriate to reference for exmaple a link rather than specific page numbers.

39Separately, under the navigation head Resources one can also find the link Reference and Source Interface where there is a database comprising about 8000 titles. I searched for ‘suffrage’ in this mask as well and found some highly interesting and relevant titles.

40From this simple search and short perusal of the relevant letters I was surprised to learn that at least for some time Mark Twain was not an avid supporter of women’s right to vote. Twain is known today as having been a progressive with regards to many topics, including women’s rights. The wikipedia page28 for Twain has just two sentences on the topic which state, ‘Twain was also a staunch supporter of women’s rights and an active campaigner for women’s suffrage. His ‘Votes for Women’ speech, in which he pressed for the granting of voting rights to women, is considered one of the most famous in history’. One sees however from our search in the MTPO letter edition and through the editor’s comments that there was personal evolution over the course of Twain’s lifetime, such that he ultimately became a ‘staunch supporter’ for women’s rights and made such an historic speech. Only in a letter from 1874, written when he was 39 years old, could I find a really positive outlook from Twain on the issue: ‘Both the great parties have failed. I wish we might have a woman’s party now, & see how that would work. I feel persuaded that in extending the suffrage to women this country could lose absolutely nothing & might gain a great deal.’29 And the footnote from the editor mentions ‘This was Clemens’s most unequivocal endorsement to date of women’s suffrage[…]’.30 The letters from later in his life are not available in the current edition, but those letters must show the full development of his viewpoint, and the viewpoint that he is better known for (he was 72 years old when he made his famous ‘Votes for Women’ speech). Looking at the letters one can better appreciate the complexities of Twain as a person and gain a glimpse at the man behind the mythical character he has since become in the eyes of history. It is refreshing to learn that someone famous for their progressive mindset had to grow into some of those views, and was not a static intellectual figure, but rather an organic and evolving one. Altogether this small test search in the letters proved fruitful and showed that the edition is ideal for this kind of research into Mark Twain’s life. The only shame is that more letters are not yet edited, preventing us from gaining a truly full picture of the man and his opinions.

Additional Resources

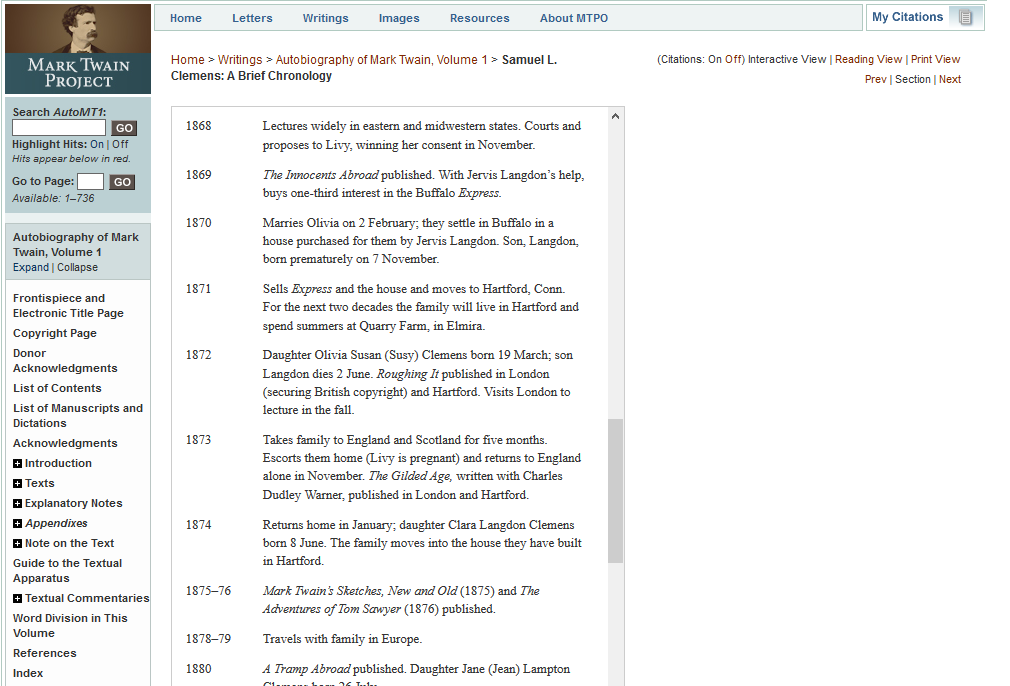

41 Under the navigational heading Resources is a list of internal supplementary material for all the editions on the website. Most of the links lead to pages that belong to particular editions of MTPO and are displayed with the same book-like, static presentation. Here one can find for instance a brief chronology of Mark Twain’s life that was included with the publication of the Autobiography, a biographical directory included with the edition of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer among the Indians and Other Unfinished Stories, as well as multiple links under the heading Photographs and Manuscripts that are from different volumes of letters.

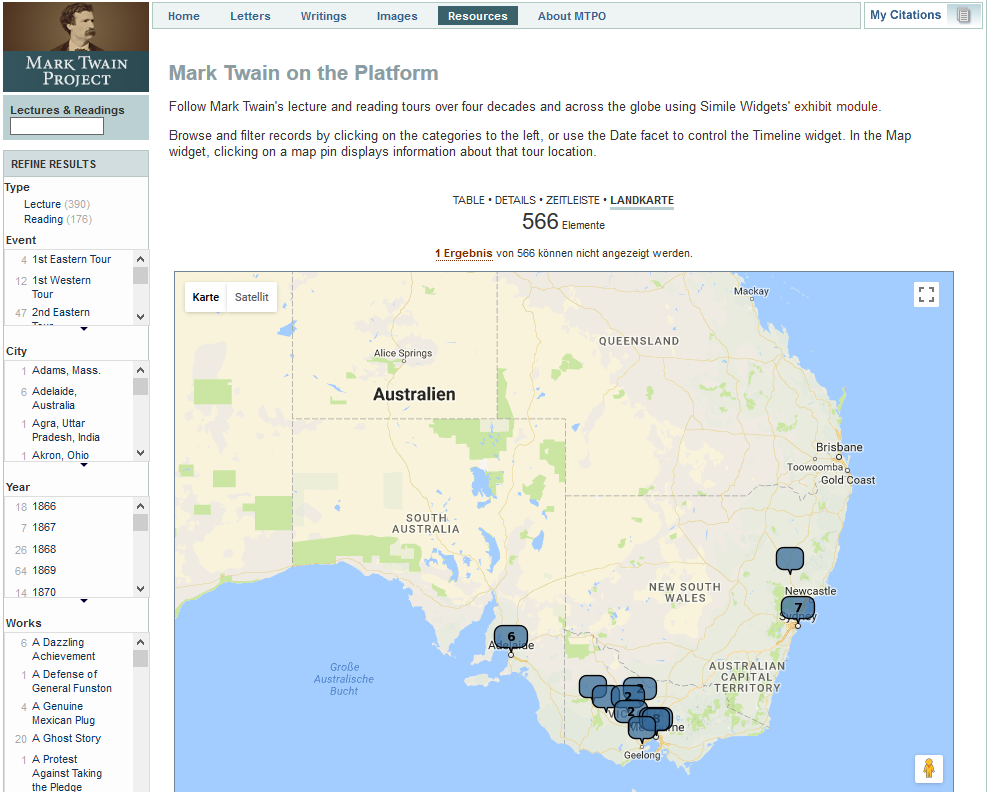

42 Of particular note within Resources is the simile exhibit, a publishing framework that creates interactive maps and timelines. The simile offers a great way to visualize Mark Twain’s extensive touring engagements. Using the map view one sees in a glance just how far he travelled (Australia!), and that he was in the city in which I live and work, Berlin, Germany, in 1892.

43Outside the Resources section there is an image database, where 250 images are available from the Mark Twain Papers archive, and 550 catalog records of images from other sources. Additionally there is a lot of project information to be found under the navigational heading About MTPO, for example the extensive and helpful User Guide or information about copyright and permissions.

44To summarize, the MTPO offers a substantial amount of supplementary material, mostly in the form of explanatory texts and additional documents. With the exception of the databases and the simile exhibit, the academic resources are presented in a static, immovable manner. They are not searchable or linked. They appear as if they were pulled from printed editions, which is often essentially what they are. Such an approach emphasizes the likeness to the form of a traditional book. The amount and quality of the information, however, is excellent.

Technical Foundation and Design

45The website was launched in 2007 and due to that fact the design is understandably outdated. Although this is occasionally distracting, it does not hinder either the reading of the letters or the use of the edition for research. There are also some nice touches, for example the clever, witty quotes from Twain which are peppered throughout the website,31 and the two letters with facsimiles displayed on both the home and main pages of the website. The design of the edited text itself and the editorial commentary is appealing and easy to read. The structure and organization of the website could use improvement, but this is most likely the result of an older navigational style. There are some links that do not work and unfortunately the citations tool sometimes generates error messages, among other small technical flaws, so some technological upkeep seems warranted. In conclusion, the display of the edition is not at the same outstanding level as the scholarly work of the edition’s content and ideally the whole website would be revamped. That said, the website is more than adequate for the usage of the edition.

46It looks as though MTPO has four main databases: one for XML files and images found in the printed editions, one for images of facsimiles amd photographs from their archive, one for metadata, and one for long term preservation. They use the open-source software eXtensible Text Framework (XTF) for the display of the edition and for the search functions. XTF was created by the California Digital Library and is a well established platform used by numerous projects. Generally the MTPO has implemented highly standardized technologies wherever possible, which has served the over ten-year old project well. It is unclear exactly which kind of databases they use and if any data migration was necessary over the years, but considering how much development there has been in the last ten years for digital editions, the MTPO seems quite up to date regarding their backend processes. They also have a system of long-term preservation in place through the California Digital Library’s Merritt32 service.

47The technical information for this review could be gathered from the project’s very extensive Technical Summary 33, found under About MTPO. The summary offers a great deal of transparency for the backend technologies. Especially impressive are the details about how TEI P4 is extended for their particular schema as well as how they have solved the problem of authorial symbols that encompass multiple lines of texts (like large brackets), which they call graphic groups. As someone who has had to deal with precisely this problem before, such information is of great interest. My only criticism here is that the quality of writing is not at the same level as the other editorial texts on the website. However, the technical summary is well-organized and includes helpful graphics and examples. To be even more transparent the project should offer the XML files for the editions as well as the schema. It is regrettable that these files are not available.34 MTPO also has an active Twitter account where they publish relevant news articles about Mark Twain and the project, and ancillary of updates. It is a great way to maintain relevance and visibility with users of the edition and other involved parties.

Conclusion

48The digital edition of Mark Twain’s Letters 1853-1880 of the Mark Twain Project Online accomplishes its aims well and is undeniably an essential edition for Mark Twain researchers, as well as an important source for historians. The level of scholarly work, the thorough commentary, and the admirable transparency make this an exemplary critical edition. The supplementary material found on the website, such as the extra resources and texts about the project, are well written with great attention to detail, and allows for various levels of knowledge. This makes the edition highly-accessible to all varieties of reader, even while being optimized for academic research.

49While the content of the letter edition and supplementary texts on the website are of the highest quality, the ‘digital’ part of the digital edition appears somewhat lacking. It would be ideal if the website were re-organized and re-designed and if a more dynamic concept were used for the digital edition and supplementary texts. To conclude, it would be thrilling if the thoroughness, modernity and meticulousness found in the text were also found in the technical execution of the edition. It is a momentous project with many writings and letters of Mark Twain still to be published, and it will be interesting to see how it develops in the coming years.

Notes

[1] Buffalo, N.Y. (UCCL 00592). In Mark Twain’s Letters, 1870–1871. Edited by Victor Fischer, Michael B. Frank, and Lin Salamo. Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1995, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20180109125039/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL00592.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[2] In this review he will be referred to as Mark Twain.

[3] Two recent headlines of many: https://web.archive.org/web/20180109125119/https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/08/books/review/purloining-prince-oleomargarine-philip-stead-mark-twain.html or https://web.archive.org/web/20180109125214/http://www2.ljworld.com/news/2017/oct/23/lawrence-school-officials-weigh-how-teach-hucklebe/.

[4] The full titles and bibliographic information of the eight letter editions can be found on the project’s electronic title page: https://web.archive.org/web/20180109122303/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/MTDP00216.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Twain_bibliography.

[6] http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_reviews.shtml.

[7] Winner of the Morton N. Cohen Award for a Distinguished Edition of Letters (for Letters, volume 6 [1874–75]) for Letters, volume 6 [1874–75], winner of the 1993–94 Modern Language Association Prize for a Distinguished Scholarly Edition for Roughing It (1993), winner of the 2010 PROSE Award for Excellence in Humanities and the 2010 California Book Awards’ Gold Medal for Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1 (2010).

[8] https://web.archive.org/web/20180109124253/https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/industry-deals/article/73067-trump-budget-calls-for-eliminating-the-nea-neh.html.

[9] See https://web.archive.org/web/20180109124516/http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_projecthistory.shtml, https://web.archive.org/web/20180109124649/http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_contributorcredits.shtml and https://web.archive.org/web/20180109124939/http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_reviews.shtml.

[10] Some additional letter facsimiles are available, these are however not linked to their corresponding edited letters. These facsimiles originate from the printed volumes’ section Photographs and Manuscript Facsimiles and are displayed as they are found in that chapter of the printed volumes. See for example https://web.archive.org/web/20180109130024/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/MTDP00305.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[11] I compared the print and digital version of letter ‘SLC to Malcolm Townsend, 22 Apr 1867, New York, N.Y. (UCCL 02444)’, In Mark Twain’s Letters, 1867–1868. https://web.archive.org/web/20180109130513/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL02444.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[12] UCCL is part of the letter identification number and stands for Union Catalog of Clemens Letters.

[13] https://web.archive.org/web/20180109131237/http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_recent.shtml.

[14] This date was not found on the website, but by looking in the first printed volume of the letters (Mark Twain’s Letters, 1853–1866) where the Guide to Editorial Practice first appeared .

[15] ‘Guide to Editorial Practice, (MTDP 00005).’ In Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20180109133140/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/MTDP00005.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[16] Fredson Bowers, ‘Transcription of Manuscripts: The Record of Variants’ Studies in Bibliography 29 (1976).

[17] http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_hirst_essay.shtml.

[18] ‘As with most scholarly editions of American authors, the editorial policies of the Mark Twain Project grew out of editorial methods and theories developed originally for editing Shakespeare’s texts.’ https://web.archive.org/web/20180109142400/http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_hirst_essay.shtml.

[19] I chose a lower quality facsimile of the kind found originally in the printed volumes (https://web.archive.org/web/20180110100803/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/MTDP00366.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp). This is because I had trouble finding a letter with a more recently made facsimile that also included editorial commentary.

[20] SLC to OLC, 11 and 12 Dec 1873, London, England (UCCL 01000).” In Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20180110100238/http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL01000.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[21] ibid.

[22] ibid.

[23] ibid.

[24] See ‘Emphasis Equivalents’ in ‘Guide to Editorial Practice, (MTDP 00005).’ In Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2007.

[25] ‘On the other hand, Clemens often did use the period and dash combined when the sentence period fell at the end of a slightly short line in his manuscript (‘period.— | New line’), a practice copied from the typographical practice of justifying short lines with an em dash. These dashes likewise do not indicate a pause and, because their function at line ends cannot be reproduced in a transcription that does not reproduce original lineation, are always emended, never transcribed.’ from ‘Guide to Editorial Practice, (MTDP 00005).’ In Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2007.

[26] Universal suffrage, for instance, was also a debated issue of the time.

[27] http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL11880.xml;query=suffrage;searchAll=yes;sectionType1=text;sectionType2=explanatorynotes;sectionType3=editorialmatter;sectionType4=textualapparatus;sectionType5=;style=letter;brand=mtp#1.

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Twain.

[29] ‘SLC to Ed., London Standard, 12 March 1874, Hartford, Conn. (UCCL 11880).’ In Mark Twain’s Letters, 1874–1875. Edited by Michael B. Frank and Harriet Elinor Smith. Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 2002, 2007. http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/vi ew?docId=letters/UCCL11880.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

[30] SLC to Ed., London Standard, 12 March 1874, Hartford, Conn. (UCCL 11880), n. 1. http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL11880.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp#an1.

[31] At the top of the page titled Peer Reviewhttp://www.marktwainproject.org/about_peerreview.shtml there is a quote from Twain: ‘One mustn’t criticise other people on grounds where he can’t stand perpendicular himself.’ (From A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Chapter XXVI).

[32] https://merritt.cdlib.org/.

[33] http://www.marktwainproject.org/about_technicalsummary.shtml.

[34] I did stumble upon this xml file from the Autobiography. It is however buried in the Recent Changes list and in no way displayed to be actually found if desired. http://www.marktwainproject.org/sample_MTDP10363.xml.

Figures

Fig. 1: Home page for MTPO.

Fig. 2: Letters Main Page for MTPO.

Fig. 3: ’The Guide to Editorial Practice’ for MTPO.

Fig. 4: ’The Guide to Editorial Practice’ as it appears in the first printed volume of ‘Mark Twain’s Letters’ in 1988.

Fig. 5: About Textual Editing at MTPO.

Fig. 6: Manuscript page 2,’SLC to OLC, 11 and 12 Dec 1873’.

Fig. 7: Manuscript page 6, ‘SLC to OLC, 11 and 12 Dec 1873’.

Fig. 8: Part of the MTPO transcription of ‘SLC to OLC, 11 and 12 Dec 1873’.

Fig. 9: Critical text of the letter for MTPO.

Fig. 10: Letter Search Mask for MTPO.

Fig. 11: Search Results Page for MTPO.

Fig. 12: A Brief Chronology of Mark Twain’s Life from MTPO.

Fig. 13: Simile Exhibit from MTPO.