By Ulrike Henny-Krahmer (Universität Würzburg), ulrike.henny (at) uni-wuerzburg.de and Frederike Neuber (University of Cologne), neuber (at) i-d-e.de. ||

1We are pleased to present the sixth issue of the Review Journal for Digital Editions and Resources (RIDE), published by the IDE since 2014, which is at the same time the first issue on Digital Text Collections (DTC). We generally define DTCs as digital resources that involve the collecting, structuring and enrichment of textual data and include in this definition DTCs from various humanities disciplines such as Literary Studies, Linguistics and History.

Motivation and scope

2From the beginning, RIDE has been conceived not only as a reviewing journal for digital scholarly editions but also for other kinds of resources with relevance for Digital Humanities, including data sets of different types, software and applications. The idea to edit an issue on DTC came up in late 2016 and was triggered by the following observations: While there is an ever growing number of projects and studies in Digital Humanities creating and using large sets of digital texts,1 the methods and practices have not yet obtained the level of standardization and best practice that has been reached in areas with a longer tradition in corpus-based studies like Linguistics, for example. Often, research on or the creation of new DTCs is based on already existing textual resources scattered among the WWW. Therefore, it is crucial to establish common standards for the documentation and provision of DTCs that support the exchange of textual data while preventing a loss of quality and reliability. Finally, at present, the various self-classifications of DTCs are ranging from “Corpus“ to “Digital archive” to “Digital library” to “Repository” to many more; each of the terms, however, can point to very different types of resources, containing very different contents and applying very different methods. This lack of a common nomenclature and classification impedes a further systematization of types of DTCs and hinders the scholarly discourse about the resources. Such a discourse, however, is desirable if DTCs are to play an ever more important role in Humanities research.

3We believe that reviewing DTCs systematically will (1) stimulate a more vivid discourse about reliability and sustainability of textual data and disseminate and canonize approved methods and approaches among disciplines; (2) help to identify and compare various methodological frameworks, and thereby provide an overview of the transfer of methods between single disciplines when building DTCs in Digital Humanities; (3) contribute to sharpen terminologies and concepts of different kinds of DTCs and in the long term lead to a more differentiated understanding of what types of “text collections” exist and in what way they differ from each other. Last but not least, we also want to raise awareness of the scholarly work involved in designing and providing DTCs.

Methodological framework

4To assure consistency and quality of the reviews on DTCs as much as for the reviews on scholarly editions that have been published in RIDE so far, we started to prepare the methodological and technical framework for RIDE Digital Text Collections (RIDE-DTC) in late 2016. RIDE-DTC complies with the standards that have been developed for academic journals. On submission, reviews were blinded and referred to at least one external peer-reviewer. Furthermore, in order to guide the reviewers when discussing the projects, we developed a catalogue of criteria that covers a variety of relevant aspects of DTCs: Criteria for Reviewing Digital Text Collections (https://www.i-d-e.de/criteria-text-collections-version-1-0).2 Besides addressing these aspects in their reviews, contributors were asked to fill out a Questionnaire that accompanies the written text as a factsheet (http://ride.i-d-e.de/questionnaire-text-collections/). RIDE-DTC encourages a global discourse on the topic. We invited reviews in English, German, Italian, Spanish and French, all reviews, however, are accompanied by an English abstract. While we first just planned a single special issue on DTCs for which we published a dedicated call for reviews,3 there were so many reactions that we decided to publish at least two subsequent issues, this one being the first of them.

5The reviews and questionnaires are encoded in XML/TEI and can be read in an HTML version on the RIDE webpage or downloaded as PDF. Citability of reviews is currently achieved through persistent URLs as well as DOIs. Finally, we also visualize some of the data gathered from the questionnaires4 and offer download-packages of all XML files and images via GitHub5 to facilitate researchers with data for their own investigations and visualisations.

Content of the issue

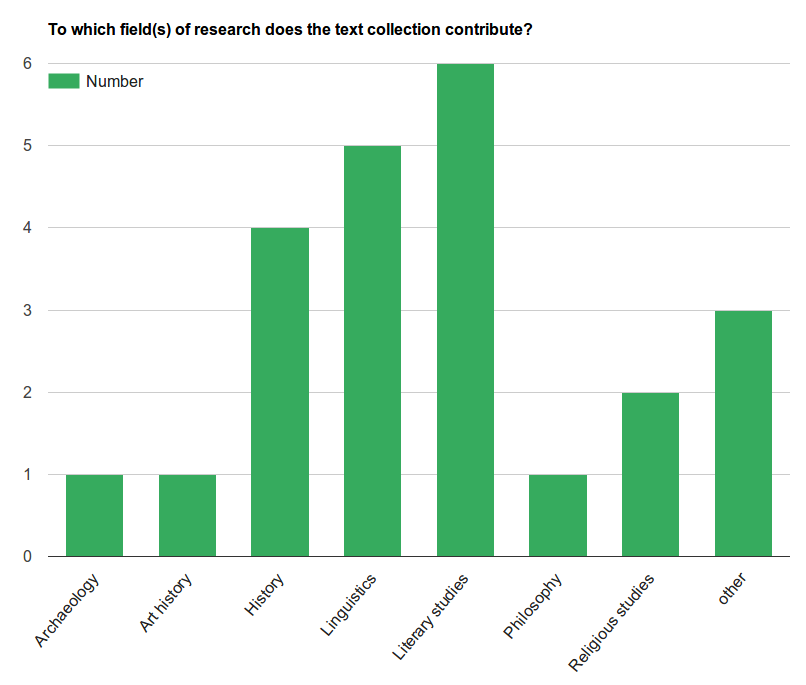

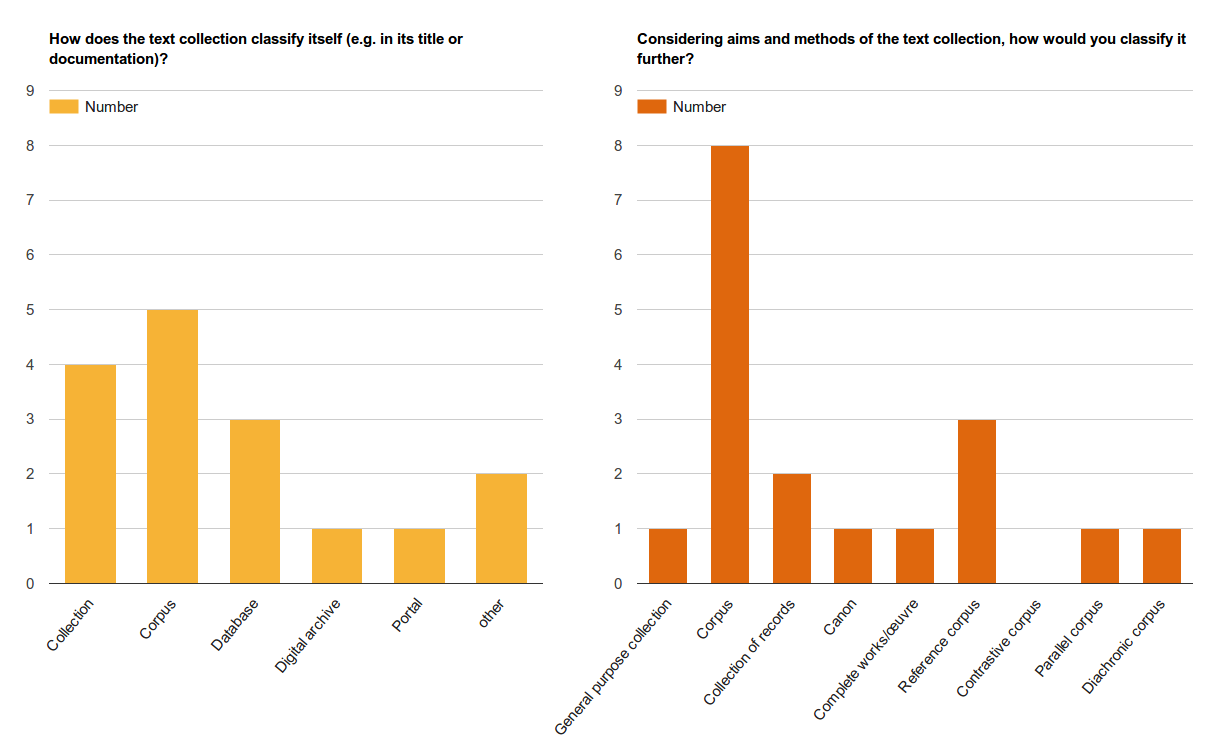

6This issue includes ten reviews which display the heterogeneity of the contents and scopes of DTCs out there. It features resources from Austria, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States of America which have been reviewed in three different languages: English (5), German (4) and Italian (1). The resources derive from various disciplinary contexts. In the questionnaire provided by us, reviewers have so far assigned the projects mainly to Literary studies, Linguistics and History (see Fig. 1).6

7The ten reviews critically asses collections that consist of texts derived from a specific type of textual carrier (e.g. books, manuscripts, newspapers) and/or texts of a specific writing genre (e.g. sonnets, essays, reviews) and/or texts that belong together because of a common historical, cultural and/or linguistic background. The way in which the textual data is modelled varies, too; from diplomatic to normalized transcriptions to summaries of texts. Almost all of the text collections reviewed are presented via a graphical user interface (GUI), usually a website, but there is also one review focusing on a text collection with a GitHub repository as the primary access point to the data. Obviously, the degree and kind of accessibility of the texts influences the way in which the resources are discussed. Ideally, both the underlying digital representation of the texts (e.g. TEI markup), as well as the presentation of specific versions of the texts (e.g. prepared reading versions on a website) can be considered in a review.

Classifying Digital Text Collections further

8As we are particularly interested in the description of different types of DTCs, we present the first results of our investigation into this topic which was carried out during the preparation of this RIDE issue. Regarding the classification of different types of text collections, we suggest a provisional typology, which is part of the questionnaire that all the reviewers filled out. While other approaches are possible, the definitions given here focus on selection criteria, scope and aim of the text collection. Also, more specific types of text collections do exist (such as a monitor corpus, for example) but are not included in an attempt to give a list of the types of DTCs that we consider “basic” from a Digital Humanities perspective:

- Basic types of DTCs:

- General purpose collection: a text collection of a very general nature (e.g. Wikisource, Project Gutenberg); often created in a collaborative fashion; with no specific or very loose selection criteria; usually not bound to a certain timeframe for its creation and completion.

- Corpus: a collection of texts that has been created according to some selection criteria (language, author, country, epoch, genre, topic, style, etc.) which makes it more specific than a general purpose collection; not necessarily aiming at completeness or representativeness; e.g. the ‘Corpus of English Religious Prose’, ‘Letters of 1916’, ‘Corpus of Literary Modernism’.

- Collection of records: a collection of texts that are held together out of organisational reasons, e.g. a collection of historical documents that has been kept in the same archive.

- Canon: collection of works that is considered most important for a certain period, culture or discipline (e.g. the biblical canon, the canon of English 19th century literature); might be formally approved or authoritative and subject to debate and revision.

- Complete works/œuvre collection of all works by a single author (e.g. complete works of Mark Twain).

- Reference corpus: corpus that has been compiled in order to be representative for a certain genre or language (e.g. reference corpus of New High German Language).

- Contrastive corpus: corpus that aims at the systematic comparison of its sub-components, to get to a description of differences and similarities between them (e.g. FinDe, a contrastive corpus of Finnish and German).

- Parallel corpus: corpus whose texts are contrasted with other versions, often translations (e.g. the Parallel Bible Corpus). A parallel corpus can be considered a certain kind of contrastive corpus.

- Diachronic corpus: corpus that reflects the evolution (e.g. of a language) over time (e.g. the Diachronic Corpus of Present-Day Spoken English (c. 1960-1980)).

Common subtypes of Corpus:

9As to typological questions, reviewers were on the one hand asked for the self-classification of the reviewed DTCs as given in their titles and documentation. On the other hand, they were asked to classify the DTC according to the typology above. For both questions (self-classification and typology), it was possible to choose multiple options as well as “other” in case none of the proposed options was perceived as fitting. The following figure shows the results for these two questions (see Fig. 2) for the DTCs reviewed in the current issue. Interestingly, eight out of ten of the text collections are considered a “Corpus” by the reviewers, while only five designate themselves as such. There are four self-branded “Collections” while only one of the text collections is classified as a “General purpose collection” and two as “Collection of records” by the reviewers. Three of the resources present themselves as “Database” and thus place the focus of their self-definition on aspects of the technical structure rather than on the methodological decisions that define the composition and goals of the respective DTC. One resource defines itself as a “Corpus” and “Digital Archive” at the same time. This raises the question whether we are talking about two different lines of classification here: one that concerns the composition of the DTC and the second that concerns aspects of the institutional curation of the project.

10These observations are helpful starting points when thinking about how to systematize DTCs further, even if due to the small sample size it is too early to draw any conclusions on this topic. However, it will be interesting to see if the differences between self-classification of the projects and the classification made by the reviewers (based on the typology we provided) persist with future issues of RIDE-DTC.

Reflections on the reviewing process in general

11When working on this RIDE issue, we were confronted with some of the general challenges that reviewing digital resources poses and which we would like to comment on: the question of “reviewability” of a resource and the possibility of productive response. Both are related to the potential open-endedness of digital publications. One of the reviews discusses two states of the resource’s graphical user-interface because the review was written in a time when the GUI was about to change and two versions of it were accessible at the same time. The historicity of a review could not be more palpable. In other cases, reviewers had been in direct contact with the editors of the resource and a discussion of future improvements of the text collection did already take place during the writing process. This is laudable, but made it sometimes hard to tell what is already there and what is going to be there as well as what is public and what is only internal knowledge and documentation of the resource. A third challenge are resources that are published in a distributed way and/or are the result of a series of research projects. Where are the boundaries of the resource that the review discusses?

12All of these phenomena stress the importance of meticulously delimiting the subject and documenting the sources of information when writing a review. They also highlight the need for citability and versioning of the resources under discussion. Certainly, these general issues about reviewing digital resources need a more comprehensive as well as detailed discussion that goes beyond this issue on DTCs and this editorial, in particular. By mentioning them, we want to stress that they actually affect the day-to-day business of reviewing. We hope that they will be picked up and discussed further by future reviewers and those generally interested in the topic of evaluation and reviewing of digital resources alike.

13Finally, although we aim at maximum consistency regarding the relevant aspects to discuss in a review of a DTC by providing a catalogue of criteria and an accompanying questionnaire, at the end of the day the content and tone of a review strongly depend on the author herself, her experiences with the source, her taste and her writing style, with the review giving room for individual judgement.

14It was interesting and encouraging to see the many reactions to our call for reviews for this RIDE issue. As a result, we welcome further contributions for a second issue on DTCs which we plan to publish in the near future.7

Enjoy the RIDE!

The editors, Ulrike Henny-Krahmer and Frederike Neuber, September 2017.

Notes

1. To name individual projects in concrete terms would lead too far. However, the fact that working with large amounts of text has become a subject of various disciplines within the DH is also shown by the increase in the number of relevant events as, for instance, the seminar series “Corpus research in linguistics and beyond” at the King’s College London (https://web.archive.org/web/20170909171938/https://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/departmen…), the symposium “Text Mining in historical science” at the German Historical Institute in Paris (https://web.archive.org/web/20170909172033/https://dhdhi.hypotheses.org/2714), the Summer School at the University of Graz on “Computergestützte Analyse und Verarbeitung von Sprache und Text – Text (and Data) Mining Methoden in der geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschung” (https://web.archive.org/web/20170909172135/https://informationsmodellierung.uni…) or the “Text Hackathon” at the Centre for Textual Studies at De Montfort University (https://web.archive.org/web/20170909172252/http://cts.dmu.ac.uk/events/hackatho…).

2. Ulrike Henny and Frederike Neuber, in collaboration with the members of the IDE. Criteria for Reviewing Digital Text Collections, version 1.0. February 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170909192316/https://www.i-d-e.de/publikationen/w…

3. https://web.archive.org/web/20170909192450/http://ride.i-d-e.de/reviewers/call-…

4. http://ride.i-d-e.de/data/charts-text-collections

5. https://github.com/i-d-e/ride/tree/issues/06

6. Multiple choices were possible.

7. See the call for reviews: http://ride.i-d-e.de/reviewers/call-for-reviews/special-issue-text-collections/