Papyri.info, Joshua Sosin (ed.), 2010. http://papyri.info (Last Accessed: 23.10.2018). Reviewed by Lucia Vannini (Institute of Classical Studies), lucia.vannini (at) postgrad.sas.ac.uk. ||

Abstract

Papyri.info, made available by the Duke University, is a text collection of over 50,000 documentary papyri, i.e., Greek and Latin documents, dating back to the IV century BC – VIII century AD, which constitute a fundamental body of evidence for ancient everyday life in the classical antiquity. The collection consists of transcriptions encoded in EpiDoc (a subset of TEI for the representation of ancient documents preserved in inscriptions and in papyri), metadata, links to related resources, and, for some records, images and translations. It also includes a platform for the scholarly community to contribute to the database, whether for the digitisation of already published material or for the proposal of new contributions, with an editorial vetting process. This review aims to illustrate the content of the collection, discussing whether the relevant information is presented in a clear way to the user; to assess the usability of the interface for searching and browsing the papyri; and to analyse the technical aspects of the resource, especially the integration of different databases and the possibility of downloading and reusing the data, while highlighting, for all these aspects, both strengths and features that could be improved.

Aims and content

1Papyri.info, launched in 2010,1 is an extensive digital text collection of Greek and Latin documentary papyri, that is, ancient documents (accounts, petitions, tax receipts, letters, etc.) dating from the IV century BC to the VIII century AD, mostly written on papyrus, and mainly discovered in archaeological excavations in Egypt.

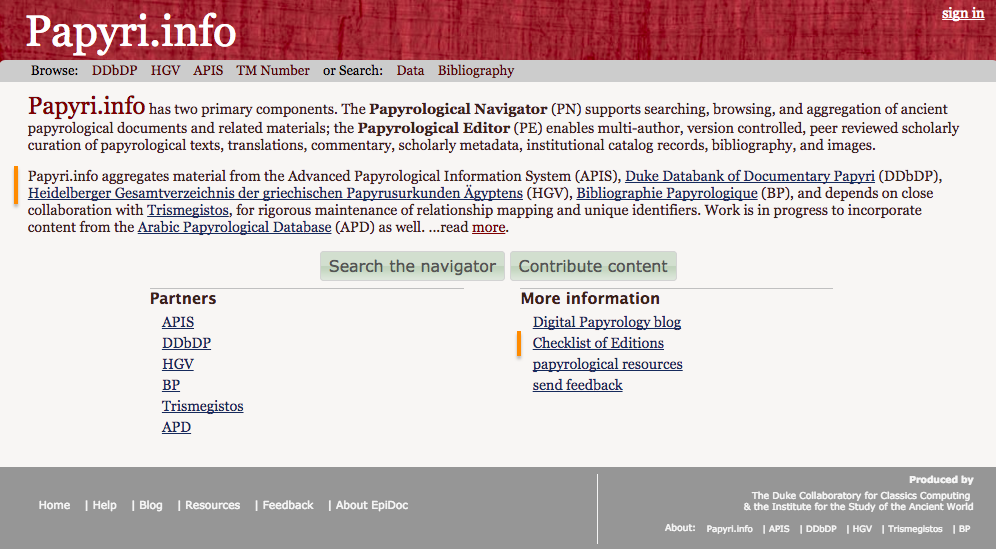

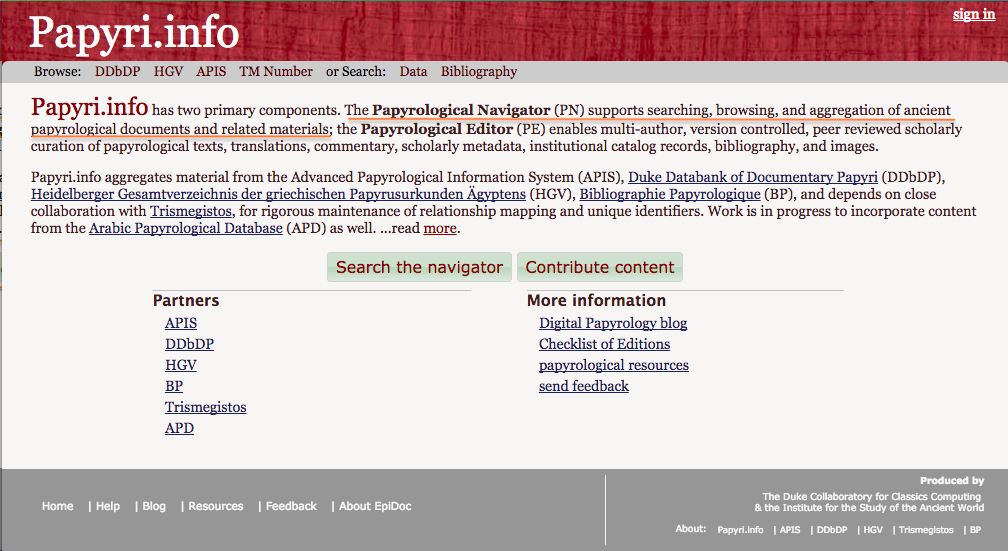

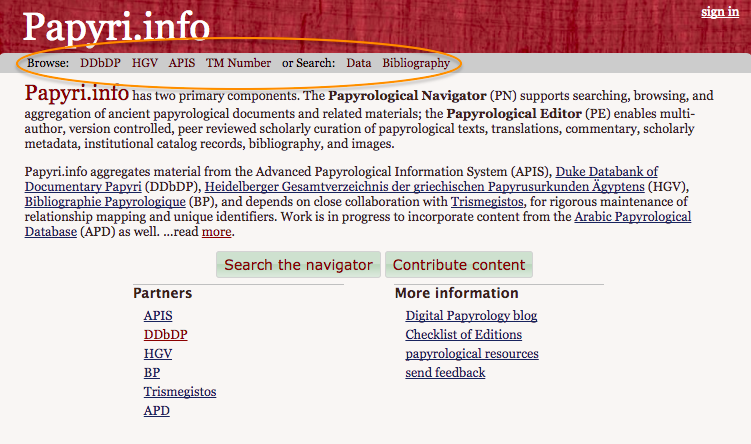

2This resource is composed of two core elements: the Papyrological Navigator (PN), a tool to browse and search the texts (on which I will therefore focus my review), and the Papyrological Editor (PE), which enables users to contribute to the collection (fig. 1). The content, i.e., the text of the papyri and their metadata, is mostly obtained from the aggregation of pre-existing databases, but also from users’ contribution: anyone can sign up and enter new texts and metadata, or edit those already existing, with a procedure that includes an editorial vetting in order to meet scholarly standards.2

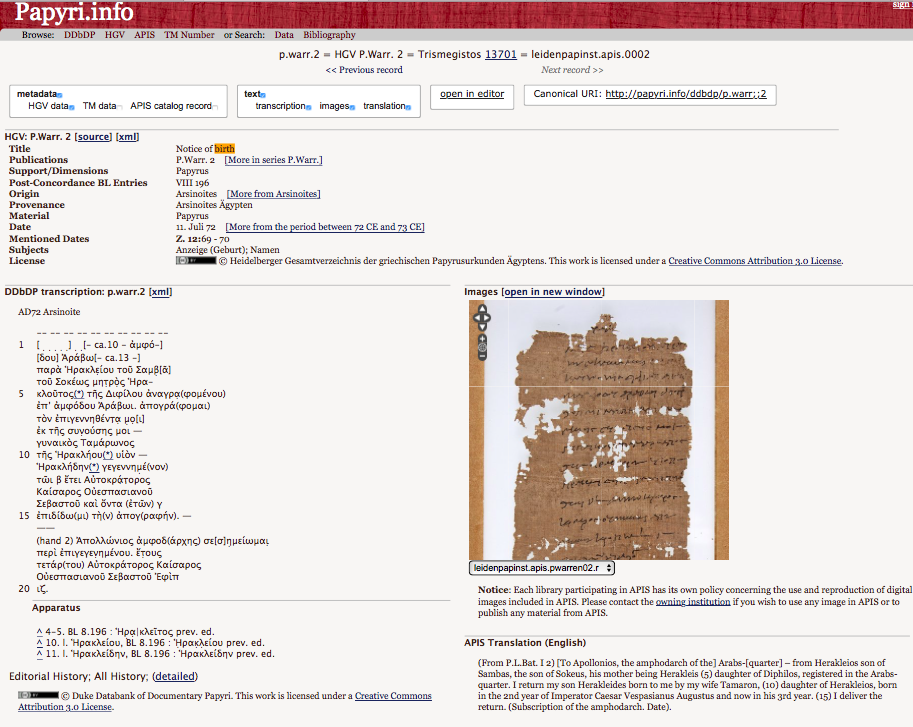

3The collection is a general purpose one, based on the principles of completeness and of representativeness, within its domain of documentary papyrology. In fact, it has become a point of reference for documentary papyrology, as it aggregates three major databases of documentary papyri: the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri (DDbDP), a very large collection of texts of documentary papyri realised by the Duke University; the Heidelberger Gesamtverzeichnis der griechischen Papyruskunden Ägyptens (HGV), created at the University of Heidelberg, which provides the metadata of all documentary papyri; and the University of Michigan Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS), focused on images, as well as metadata, of papyri from the North American institutions, plus a few small federated collections worldwide3; also important is the integration of an essential tool for papyrological research, namely its main bibliographical database, the Bibliographie Papyrologique (BP). The aims of completeness and representativeness are not explicitly stated on the Papyri.info website. We find a mention of the collection content on the home page, but this presents no information on its extension: “The Papyrological Navigator (PN) supports searching, browsing, and aggregation of ancient papyrological documents and related materials”. Notwithstanding, we can infer that completeness is a principle of the collection from the words of one of the founders of the DDbDP, John F. Oates (1993, 62): “We are aiming to construct a machine-readable data bank comprising all published Greek and Latin documentary papyri”. Also, the contributions published by William H. Willis, co-founder of the DDbDP with Oates, on the plan of the entering of the texts and on the updates on this progress demonstrate the intention that the collection may be as complete as possible: firstly they digitised the papyri published in the more recent volumes of papyrological collections, secondly the remaining volumes “in reverse chronological order until all are done”, thirdly “all texts published separately in journals”, and lastly the most significant corrections gathered in the dedicated papyrological tool, the Berichtigungsliste (Willis 1984, 172; updates on the progress of the data entry are provided in Willis 1988, 1992, 1994). The collection currently amounts to 55,080 texts, which have been merged from the DDbDP, each of them provided with metadata exported from the HGV and also, as to papyri from American collections, from the APIS. In addition to these records with the papyrus texts, there are 31,936 records with metadata only, exported from the HGV and APIS; these records pertain to published papyri whose texts have not been digitised yet, or to unpublished papyri whose metadata and images have been put at disposal by the APIS researches to enable the scholarly community to study them.4 Finally, as just mentioned, there are images of some papyri, exported from the APIS database, and therefore pertaining to fragments mostly housed in American institutions.5

4The collection is meant to be used in research, especially by papyrologists or by ancient historians who need to consult papyrological primary and secondary sources. Besides the fields of papyrology and ancient history, the collection contributes to historical linguistics, helping scholars to examine the features of the language of the papyri – texts that constitute an important body of evidence for Greek and Latin in their postclassical phases, and for their contacts with other languages of the Mediterranean.6 Papyri.info intends to meet scholarly standards by submitting the texts and the changes entered by users to an editorial vetting, and by reporting the emendations and the supplements (both already published and newly proposed by users) of the text transcriptions.

Participating institutions and staff, and their bibliographic identification

5Several institutions were involved in the development of Papyri.info. The Duke Collaboratory for Classics Computing (DC3) of the Duke University, to which Ryan Baumann, Hugh Cayless and Josh Sosin belong, and the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), in particular Roger Bagnall (formerly based at the Columbia University) are mentioned in this resource as the producers, on the home page and on the “About” page (figg. 2 and 3).

6As well as these, more institutions were responsible for the development of this resource. Their role is however acknowledged only on the page about the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri (DDbDP, fig. 4); as their names do not appear on the home page, nor on the “About” page, they are therefore little visible.

7The then Centre for Computing in the Humanities, now Department of Digital Humanities, at King’s College London, was in charge of the first round of conversion from Beta Code into the Unicode character encoding, and from SGML into the EpiDoc XML standard (Bodard, Sosin, and Viglianti 2011). The Heidelberg Institut für Papyrologie mapped its HGV database with the other databases of papyri aggregated into Papyri.info, namely the DDbDP and APIS7, and, also currently, works for continuing the integration of the HGV metadata of new papyri into the PN8; also, James Cowey in Heidelberg is co-director of the DDbDP together with Joshua Sosin, as reported on the information page of the DDbDP (fig. 4). All this information reported on the DDbDP page is also very relevant to Papyri.info as a whole, as the texts, which it contributed, constitute the core of the PN. Furthermore, this page contains details on the editorial board who approves users’ contributions, and it thus concerns the current state of the collection as well. As King’s College London and the Institut für Papyrologie, too, gave a contribution to Papyri.info, and the latter still continues to collaborate, their role should be put in more evidence, and be as visible as the mention of the DC3 and the ISAW. Hence, King’s College London and the Institut für Papyrologie, too, should occur on the home page and in the history of the development of Papyri.info on the “About” page (fig. 3), and at least the HGV should be reported on the home page under the heading “Produced by” (at the bottom, on the right: see fig. 2). Other involved institutions mentioned on the “DDbDP” page, which should occur on the “About” page of Papyri.info, are the Columbia University Libraries, the University of North Carolina, the University of Kentucky and the New York University. Alternatively, the two pages about Papyri.info and the DDbDP could be merged into a single page.

8Funding was provided by the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), as reported on the “About” page. Furthermore, from the “DDbDP” page we learn that financial support was granted to the Duke Databank by the Packard Foundation and the Packard Humanities Institute (PHI). As already noted, since Papyri.info has its roots in the DDbDP and therefore their histories are closely connected, it would be fair to mention the Packard funding in the “About papyri.info” page, as well: without the initial support from the Packard institutions, who also gave technical assistance, many of the texts that now populate the database could not have been entered.9

9As for the long-term archiving of the data and institutional curation, information is provided, on the “About” page (in the “Stewardship” section) about the Duke Collaboratory for Classics Computing, based at the Duke University Library, reported as the unit who has the task of the “maintenance and enhancement of the papyri.info toolset and community”. More details on the way the sustainability of Papyri.info is pursued are available in the related bibliography: open source development, through the use of a Git repository to store and update the data (Papyri.info IDP (Integrating Digital Papyrology) Data, https://web.archive.org/web/20180202152933/https://github.com/papyri/idp.data; standards-based formats, i.e., the Unicode character encoding, EpiDoc-conformant TEI markup, and the Resource Description Framework (RDF) model for the integration of the databases in the context of the Semantic Web.10

10In conclusion, information about the creators and the participating institutions that provided expertise and funding is presented; on the other hand, it needs to be made more discoverable by integrating it into the information about the whole resource, rather than being referred to just in connection with one of its compounds. More details on the long-term data preservation, which are found in the bibliography on the project, could be added to the “About” page for any user interested in following up in the reasons of the choices made by the developers; as an alternative, users could be provided with the bibliographical references where this information can be found.

The integration of multiple papyrological resources

The different kinds of source databases

11The Papyrological Navigator (PN) is formed by the aggregation of three pre-existing databases (as anticipated): while the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri (DDbDP), which provided the texts of the papyri, is now merged into the PN, the two other resources that have been integrated into it, namely the Heidelberger Gesamtverzeichnis der griechischen Papyruskunden Ägyptens (HGV) and the Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS), continue to exist independently. After the integration process of the HGV and APIS, updates in the HGV (i.e., metadata of newly published papyri or corrections to the metadata already existing) continue to be entered into the PN. James Cowey (Institut für Papyrologie of the University of Heidelberg), who is both editor of the HGV and co-director of the DDbDP, is the person responsible for updating the HGV and for exporting this data into GitHub, with the technical assistance of Carmen Lanz (of the Institut für Papyrologie as well). They report the changes to the researchers of the Duke Collaboratory for Classics Computing (Ryan Baumann, Hugh Cayless and Joshua Sosin), who are in charge for the maintenance of Papyri.info, so that they can merge the updates from GitHub into the Papyri.info branch. Since the data of the HGV are maintained and updated in a FileMaker database, whereas Papyri.info is an XML based project, the XML export possibility of FileMaker is used to crosswalk the data to XML, before adding them to GitHub.11

12As opposed to this, updates in the APIS are unfortunately not visible in the PN.12 The fact that the PN receives updates from the HGV implies that we obtain the same results if we perform the same search on the two databases. However, more precisely, the number of hits of the HGV can be slightly higher, because a text may have been reported on two or three different records if its dating is uncertain or if a papyrus contains more than one date (the latter happens when, after being reused, a papyrus is composed by separate texts copied in different moments); in this case, the PN instead records the dates, or a time span, in the “Date” field of the papyrus record.13 Furthermore, if the same fragment contains two or more texts written by different scribes, whether with a date or not, the HGV, again, treats them as distinct items and uses a record for each of them, whereas the PN presents the texts in only one record.14 An opposite treatment is instead assigned to papyri that preserve two or more different texts, which are however written by the same hand and published together in the same edition: the PN considers them as a single item, assigning them to only one record, while the HGV stores each text in a different record.15 One should then resort to the PN database rather than to the HGV, if one intends to obtain exact numerical data for statistical purposes. On the other hand, users may wish to resort to the HGV in some cases, as its user interface allows more possibilities of search and more specific searches within the dating field (see below).

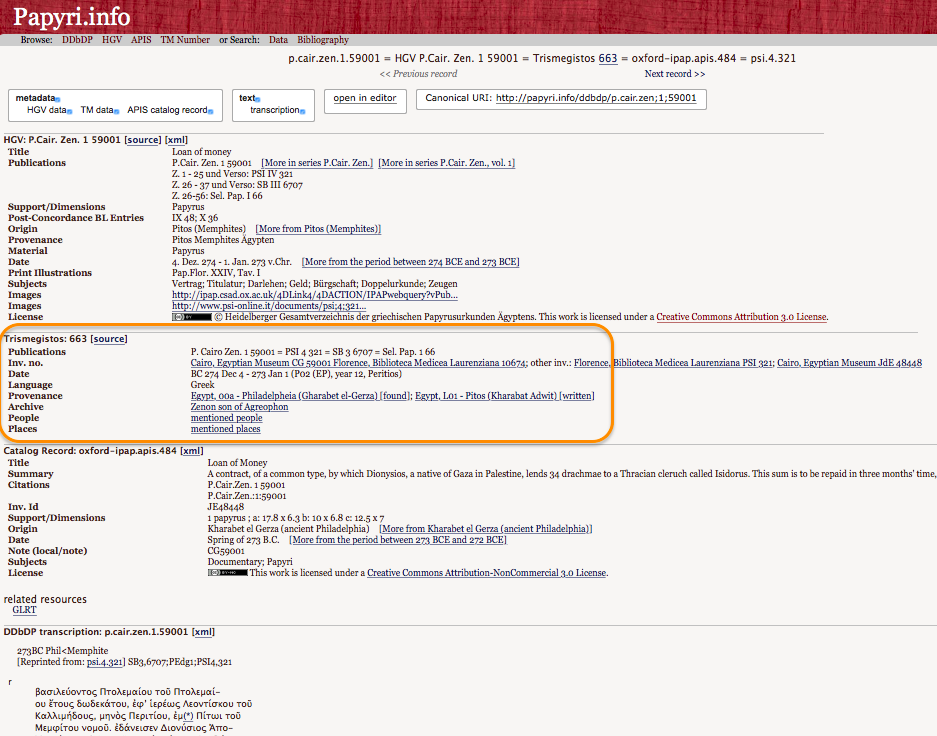

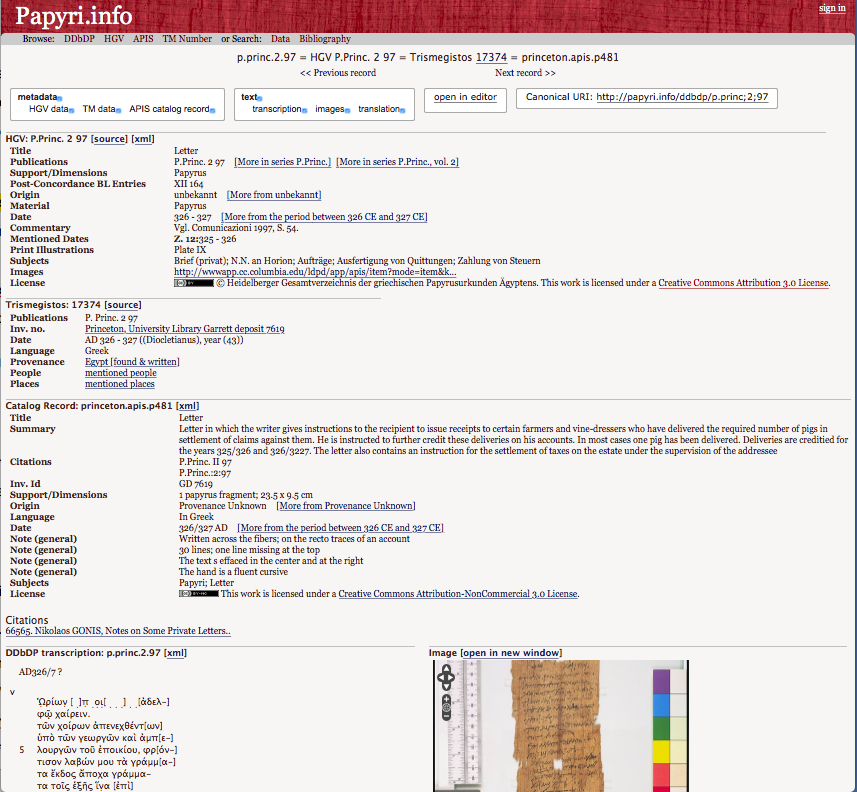

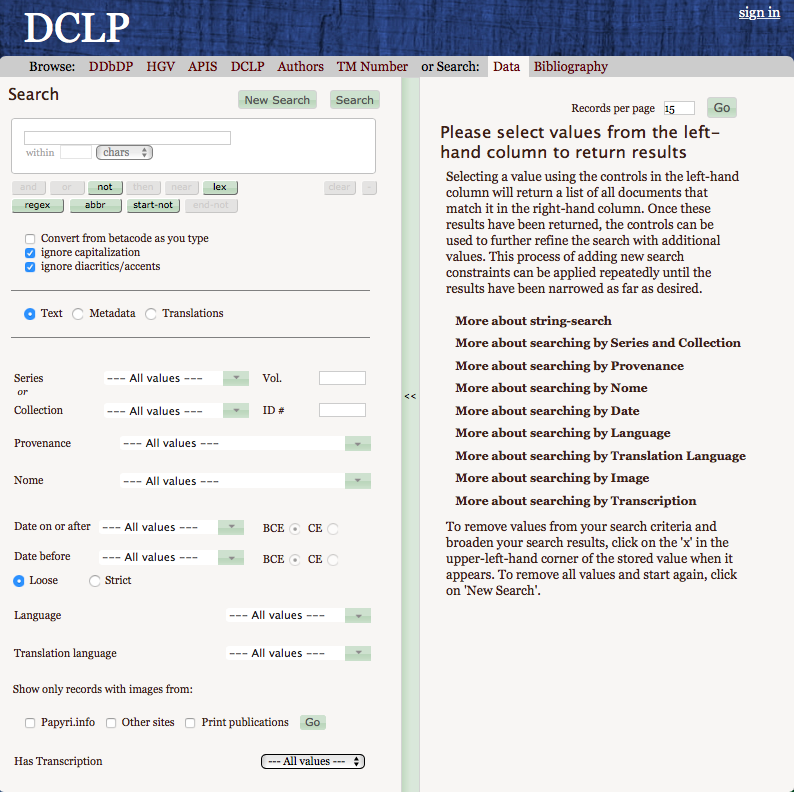

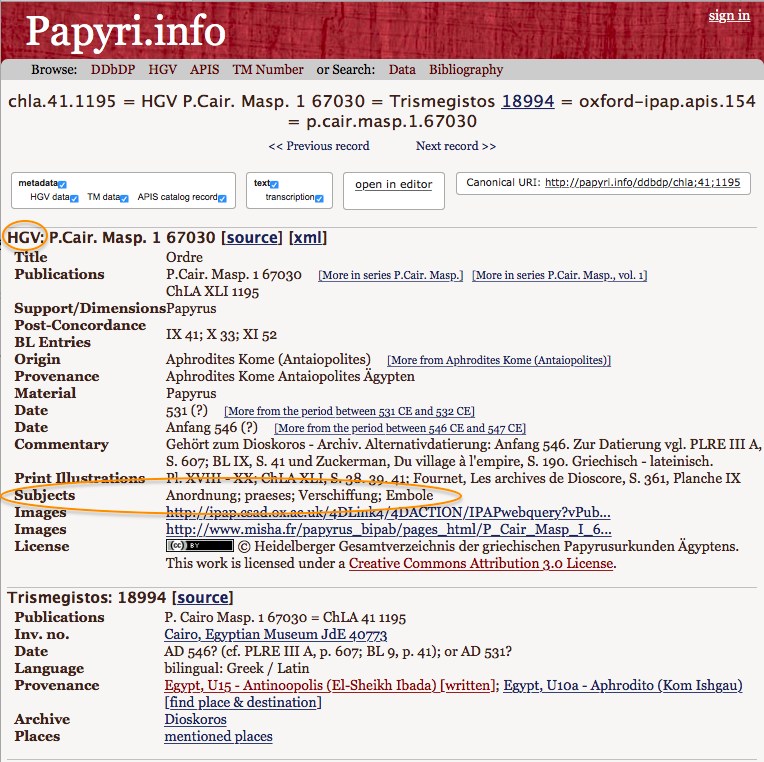

13The integration with the Trismegistos database (a platform with metadata of ancient texts, in a wide variety of languages and on different supports) allows users to access this resource through links in PN records. One can thus gain further information on the place of provenance of a papyrus, on the collection that currently houses it, on the people and the places mentioned in the text, and on the possible ancient archive the fragment belonged to originally.

14In the records of the PN we can thus find texts, metadata, and images or links to images (provided that images are available on APIS or other databases, usually those of the physical collections).

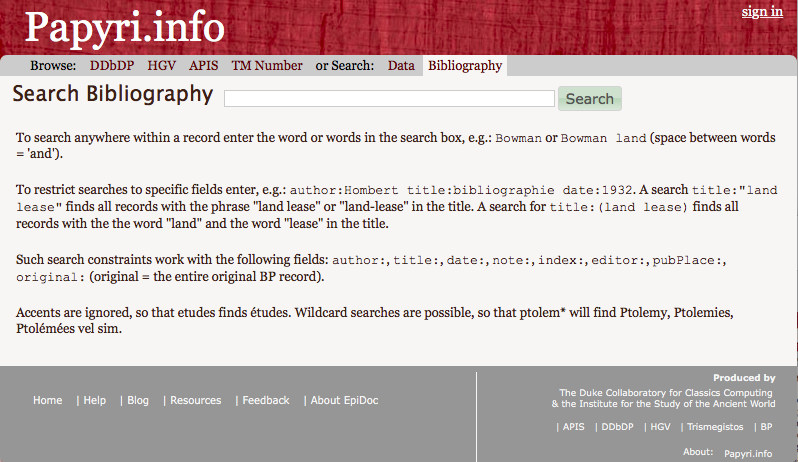

15In addition to this data, the PN includes the most important database of bibliographical information for papyri, the Bibliographie Papyrologique (BP). It should be noted, however, that this source is not clearly stated: the aggregation of the BP, though pointed out on the home page within the information about the related projects (fig. 9), is however not included in the “Search Bibliography” form (fig. 10). Given that the bibliographical database is indicated as “Bibliography” both in the “Search Bibliography” form and in the menu bar, there is no way for the user to know that it is formed by the BP except reading the information about Papyri.info on the home page; they may however skip this step to go directly to the “Search Bibliography” form or to the “Search” form. A user I interviewed for my research, who stated that he prefers to consult the papyrological bibliography on Papyri.info rather than on the BP, was in fact not aware of the relationship between the two databases. Regarding this bibliographical database, users should also be informed that the BP records later than 2012 are not available in the PN, as one can only learn from the Bibliographie Papyrologique website.16 This issue is indicative of the advantages, but also of the risks, entailed by the integration of different sources into one platform. On one hand, it is possible to create links between the record of a papyrus and the bibliographical record, to allow adding new bibliographical information or editing the existing records, and creating stable URLs to indicate a bibliographical entry – features that are not possible on the BP database.17 On the other hand, there is a need for transparency for the provenance of the data: the source databases should be clearly indicated and regularly updated, or at least their updating status should be stated.

16Finally, the Papyrological Navigator includes a Checklist of Editions, a list of papyrological editions and instruments also used as a reference for standard abbreviations. The presence of the Checklist, however, needs to be highlighted more on the home page: as a research tool, it should be distinguished from the other, as much as useful, resources indicated in the “More information” column of the home page, namely the Digital Papyrology blog, a list of papyrological resources, and indications for sending feedback (fig. 9). The link to the Checklist could be positioned next to the “Bibliography”, in the menu bar on top. Also, the presence of the Checklist should be mentioned in the information about the material aggregated into Papyri.info, at least on the “About” page18, and possibly on the home page as well.

17Regarding the mentioned Digital Papyrology blog, since its last update dates back to 2012, it seems more appropriate to include its link on the Papyri.info “About” page, indicating that this blog provides further details on the development of the resource: most posts concern updates on the functionalities of Papyri.info and the related TM database, and thus constitute a source of information for the history of the project.19

18To sum up, the material merged, integrated, or linked with the Papyrological Navigator provides a very extensive collection of texts of the chosen kind, i.e., documentary papyri, along with comprehensive information and aids for papyrological research. However, it would be necessary to inform users in a clearer and more precise way about the characteristics of its material, as noted above about the source of the “Bibliography” and the status of its update, and the presence of the Checklist. But, even more important, a key information that is not provided concerns the kind of papyri included in the collection, as there is no clear indication that Papyri.info concerns documentary papyri and not literary ones. The home page contains the information “The Papyrological Navigator (PN) supports searching, browsing, and aggregation of ancient papyrological documents and related materials” (fig. 11); however, the phrase “ancient papyrological documents and related materials” rather than “documentary papyri” may indicate, more in general, all kinds of papyri, including literary and paraliterary ones. Since the name of the resource does not contain a reference to the documentary character of the collection either, this essential information ought to be stated at the very beginning of the home page.20

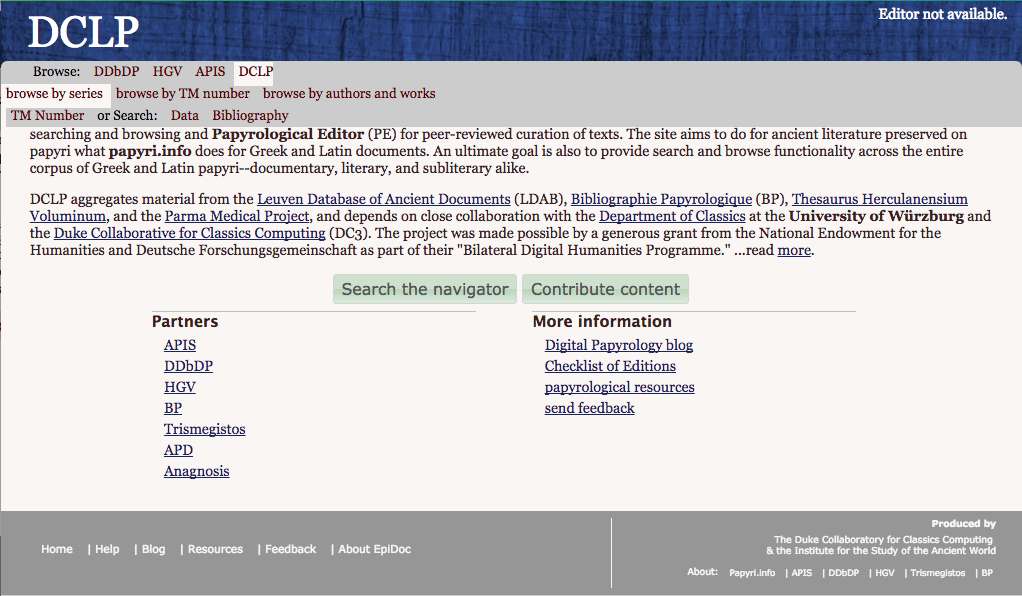

Issues in the collection content

19Searches among the metadata show that there are also a few non-documentary papyri, i.e., literary, medical and magical texts (they can be found by entering “literary”, “magical” and “medical” in the Search form and selecting the “Metadata” option), even though these categories are now being systematically published in a separate corpus, the Digital Corpus of Literary Papyri (DCLP) developed at the University of Heidelberg.21 It seems that, in part, these extra texts belong to one of the source databanks included in Papyri.info, i.e., the Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS), since many of them are housed in American collections. As to the medical papyri, they were first included into the Papyrological Navigator (within the Digital Corpus of the Greek Medical Papyri project of the University of Parma22) and only in a second moment they have been exported to the DCLP, where they now are being added;23 the first digitised medical papyri seem therefore to have remained in the PN. It would be opportune to remove these texts, which are duplicates of DCLP records, and whose presence can affect the results of searches in Papyri.info made for statistical purposes. At least, their existence in Papyri.info should be pointed out to users, who should also be suggested to search the DCLP for specific queries among those categories, for more complete results. Finally, it would be at any rate useful to add the information about the DCLP on the Papyri.info home page, since they are two separate but similar projects, both with regards to content and technical implementation.

20While the content types are not precisely stated, there is a clear classification of the content from the point of view of the print series and collections in which the texts have been published: one can find them by browsing the three aggregated databases (DDbDP, HGV and APIS) from the menu bar (figg. 14, 15). However, this classification, which is useful to find a papyrus by its edition abbreviation, cannot be used to find types of content, as these cannot be inferred from the publication series. It would be helpful to add, in the search form, a “content type” or “subject” field, by which to search the “subject” field present in the papyri records (derived from the “Inhalt” field of the HGV source database, as discussed below).

Usage and reuse scenarios of the collection

Usage for word-searches

21When it was created, the goal of the collection was to speed word searches in order to find textual parallels and documents of the same type more quickly: this helps scholars to propose supplements, carry out a linguistic analysis, and study documents according to their different typologies. Such objectives, set out by the founders of the Duke Databank, John Oates and William Willis,24 still today represent the main type of usage of the collection: the users I have interviewed for my research so far25 have mentioned these purposes as the reasons why they avail themselves of the Papyrological Navigator in their everyday scholarly activities.

22Other kinds of searches for which the collection can be used, as users point out, are those of scribal mistakes and abbreviations. The ability to search for mistakes is useful to check the validity of a conjecture when one suspects that, in one’s own editorial work with documentary texts, a damaged line contained, in the gap, a misspelled word: since the original form employed by the scribe is always reported in the texts in Papyri.info (as well as the normalised one), the user can look up the incorrect word they have conjectured, to verify whether it is a mistake commonly attested in papyri. As regards the search for abbreviations, this is useful to understand how an abbreviation found in one’s text could be expanded; this search is possible because both the abbreviated word reported by the scribe and the expanded form restored by the editor are indicated in the texts in Papyri.info, and because the search form includes the possibility to specifically search for abbreviations (fig. 16).

The EpiDoc encoding standard

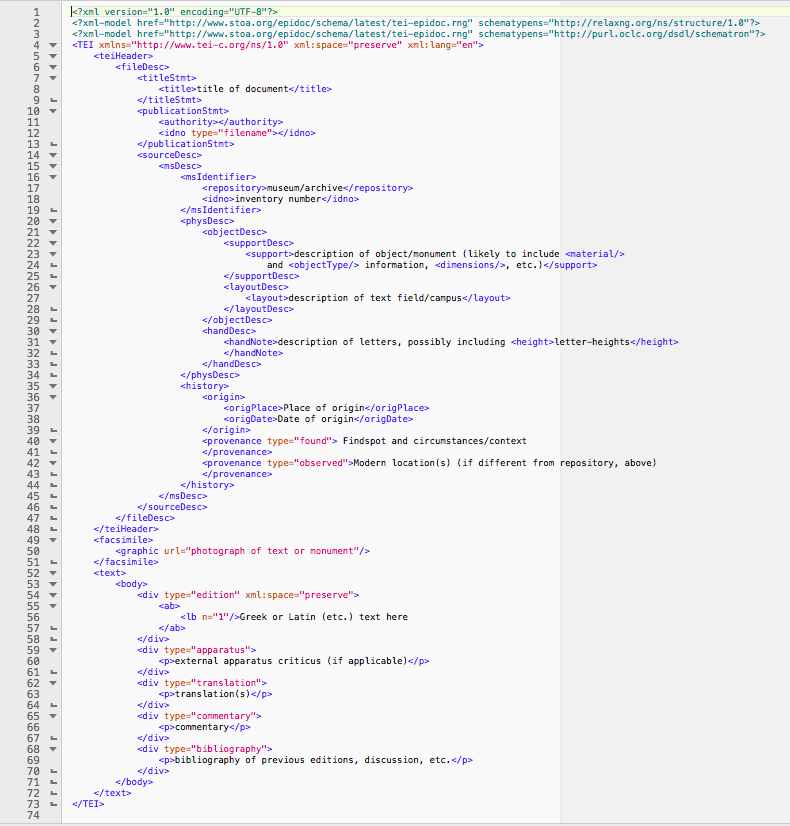

23Another function, which instead could not have been foreseen in the age when the Duke Databank was founded, is to allow the reuse of its data for new purposes, enabled by the introduction of standards-based encoding formats. Namely, the PN database also works as a textual repository, in that it can provide text data for further collection-external research. In fact, its texts are encoded in the standard EpiDoc markup, a set of guidelines for the digital representation of ancient texts of inscriptions and papyri, based on TEI elements and attributes, which has been employed in a variety of projects.26 The texts have been converted to EpiDoc when the source databanks were integrated into Papyri.info, in the Integrating Digital Papyrology project.27

24The EpiDoc model has been created to represent in digital form the texts that are traditionally transcribed according to the 1932 Leiden editorial conventions.28 These texts, inscriptions and papyri, are ancient documents of direct tradition, i.e., discovered in archaeological excavations rather than handed down to us through medieval tradition. This implies the advantage of their chronological closeness to the ancient historical events and literary works, but also the problem of their severely damaged state of preservation. Hence the necessity to develop such a system as the Leiden Convention: this allows accounting for the physical appearance of the texts and for the editorial decisions taken in the restoration of the missing words and in the interpretation of the signs employed by the ancient scribes. Examples from the Leiden transcription style are the square brackets that surround the letters lost in a lacuna and restored by the editor, the dots under the line to indicate letters of uncertain reading, and round brackets to expand a word written in abbreviation by the scribe.

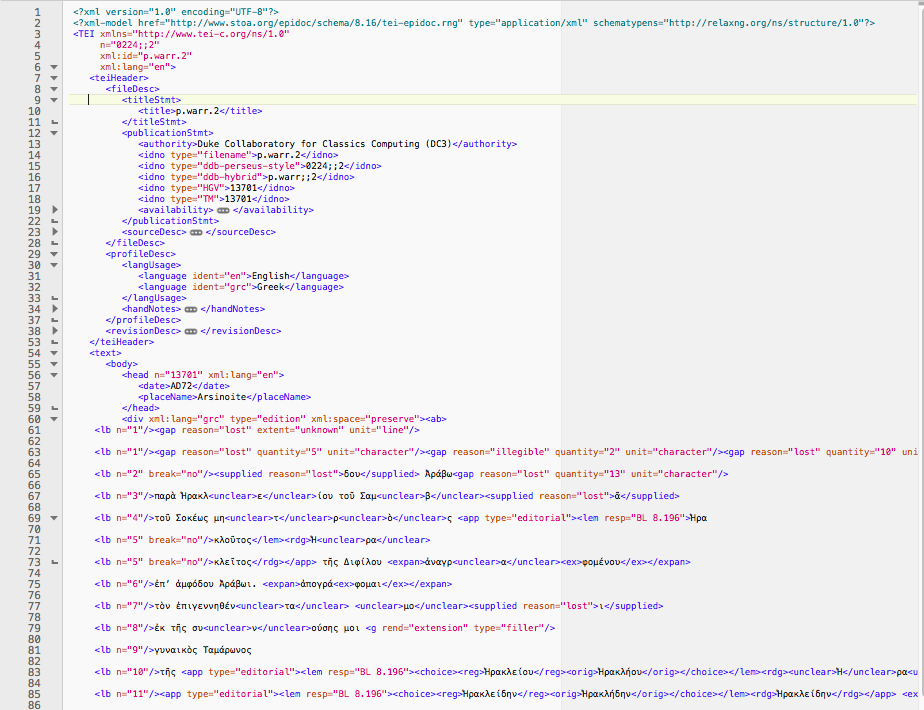

25By customising the TEI guidelines for the needs of epigraphists and papyrologists, the EpiDoc markup aims at representing the information conveyed by the Leiden signs, as well as at encoding the features of the history and of the materiality of the object. For encoding the item description, the <teiHeader> element of an EpiDoc file contains a <sourceDesc> element, which marks information about the institution that houses the papyrus or inscription, the inventory number, the support that bears the writing, the layout, the hand, the place of origin and the date (see fig. 17 for the template with the basic structure of an EpiDoc file; this is downloadable from https://sourceforge.net/p/epidoc/wiki/Examples/ (accessed 11 January 2018). After the <teiHeader>, the <text> element contains <div> elements for the different parts of the edition: text (enclosed by a further element, <ab>), apparatus, translation, commentary and bibliography.

26As we can see in the example of an XML file of a papyrus text in Papyri.info (fig. 18 and 19), the square brackets that indicate a lacuna in the text, e.g. of five letters in line 1, are rendered with the XML tag <gap reason=”lost” quantity=”5″ unit=”character”/>; an uncertain letter, e.g. ε in line 3, is enclosed within the <unclear> tag, and will be displayed in Papyri.info with a dot under the letter, as according to the Leiden convention; abbreviations are rendered by surrounding the whole expanded word with the <expan> tag, and adding a further tag, <ex> around the letters omitted by the scribe.

27The XML files of Papyri.info have a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence, which allows free adaptation of the material for scholarly reuse.29 The collection has recently started being exploited in this sense, even though there are still few examples of this use, which obviously requires higher technical skills. One needs to download the XML files of the texts, which can be done both for single papyri and for the collection as a whole. Texts can be downloaded individually by clicking on the “xml” link in the transcription heading of each papyrus record. Otherwise, one can download the entire collection from the GitHub data repository of Papyri.info (Papyri.info IDP (Integrating Digital Papyrology) Data, https://web.archive.org/web/20180202152933/https://github.com/papyri/idp.data). Here the XML files of the texts are contained in the “DDB_EpiDoc_XML” folder, grouped in bundles according to the publication volumes; a bundle with the texts provided with translations in English or German is also available from the GitHub repository, by the name “HGV_trans_EpiDoc”. While the decision to make this and all the other data of Papyri.info publicly available ensures transparency and allows a variety of scholarly reuses, the possibility to download of the texts could be more flexible and more clearly indicated. Ideally, it should be possible to download a bundle of selected files as well, besides those grouped by their publication volume and those that include translations. Also, a link to the GitHub repository should be provided, as there is currently no way to know about the possibility of downloading all the texts in one bundle or the translations (as well as the files of the metadata, the bibliography, some Arabic papyri, and the RDF data).30

Projects that reuse the content of Papyri.info

28The University of Helsinki Sematia project31 is utilising texts downloaded from Papyri.info to build up a corpus of treebanked Greek documentary papyri. After being downloaded, the texts are enriched with morpho-syntactic annotation, carried out with the Arethusa tool on the Perseids platform. The corpus will enable the analysis of the linguistic structures of the texts on an extensive scale, and will facilitate comparisons between the scribes’ original text (with mistakes, peculiar spellings, and non-expanded abbreviations) and the standard Greek, and between different scribes’ spellings. Another example of reuse of the collection for the needs of one’s research is a project that is being carried out for a doctoral dissertation in the Department of Linguistics of the KU Leuven, by Alek Keersmaekers. Like in the Sematia project, he is using the material downloaded from the PN to create a corpus of morphologically annotated texts of documentary papyri; however, in Sematia the linguistic annotation is carried out manually, whereas Keersmaekers performs it automatically on the basis of machine learning techniques.32

29The possibility of downloading the EpiDoc XML files with the texts and metadata and to repurpose the collection to other researches’ ends obviates the issue of the lack of linguistic or semantic annotation, sometimes pointed out by users.33 In fact, the texts of Papyri.info have been used in the Trismegistos (TM) platform to create databases of person and place names, respectively TM People and TM Places: a computer-aided extraction of these categories of nouns was applied to the downloaded texts, starting from the automatic filtering of capitalised words.34 Recently, Trismegistos added to its platform a new database, TM Words35, developed in cooperation with Alek Keersmaekers, again created on the basis of the XML version of the Papyri.info texts available on GitHub: it contains all the words attested in papyri in the texts on Papyri.info, and they are searchable by lemmata and conjugated or declined forms.

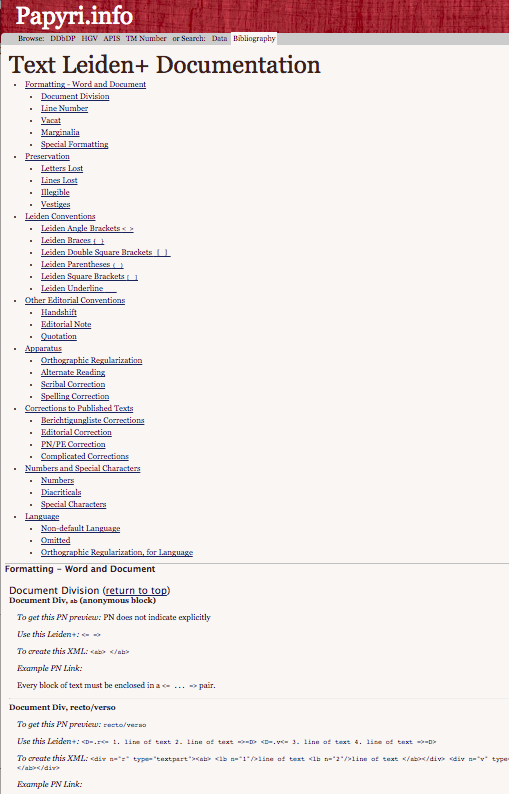

30A minor problem encountered in downloading the texts, experienced by Alek Keersmaekers for his research and by myself when importing a text to Arethusa to carry out the linguistic annotation for Sematia, is the necessity to sometimes split up words manually, as the space for the word division can be missing in the XML files of the texts. This issue occurs whenever the end of a word coincides with the end of a line in the papyrus text. Regarding this problem, it can be mentioned that there are currently no guidelines in Papyri.info on how to enter texts with the Papyrological Editor; as much as the “Text Leiden+ Documentation” (the complete list of markup signs for encoding the texts)36 is of great help, it would be convenient to add guidelines so as to provide users with indications on the whole encoding procedure of a text, especially those who have not attended an EpiDoc workshop or might need to recollect the procedure after some time. Within these directions, it could be suggested to contributors to add a space after the word endings that occur at the end of a line: this detail, which entails no difference in the text publication, would however ensure a correct word division in the XML files whenever they are downloaded.

The user interface of the Papyrological Navigator (PN)

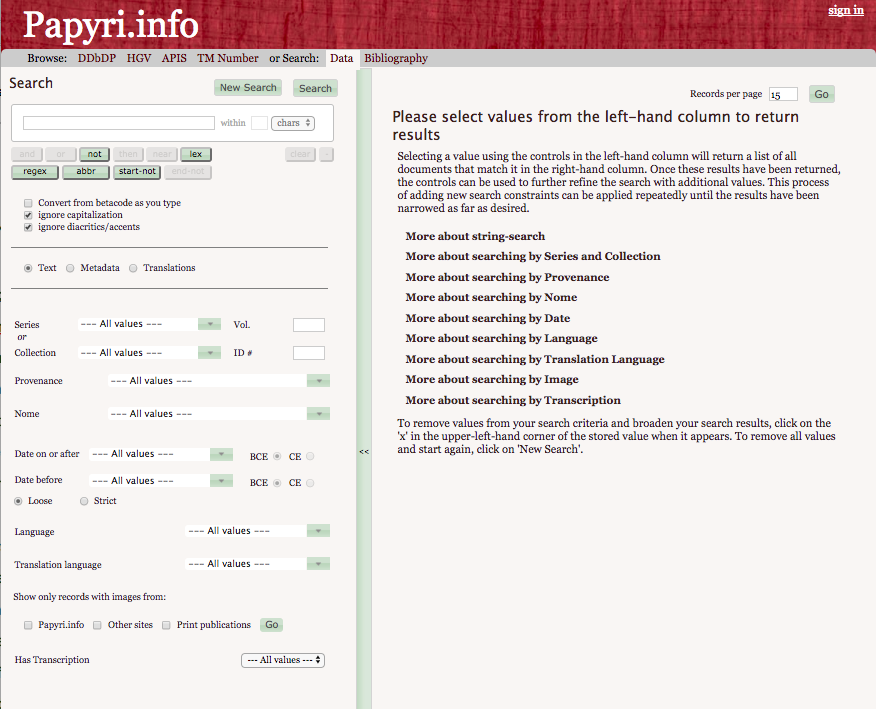

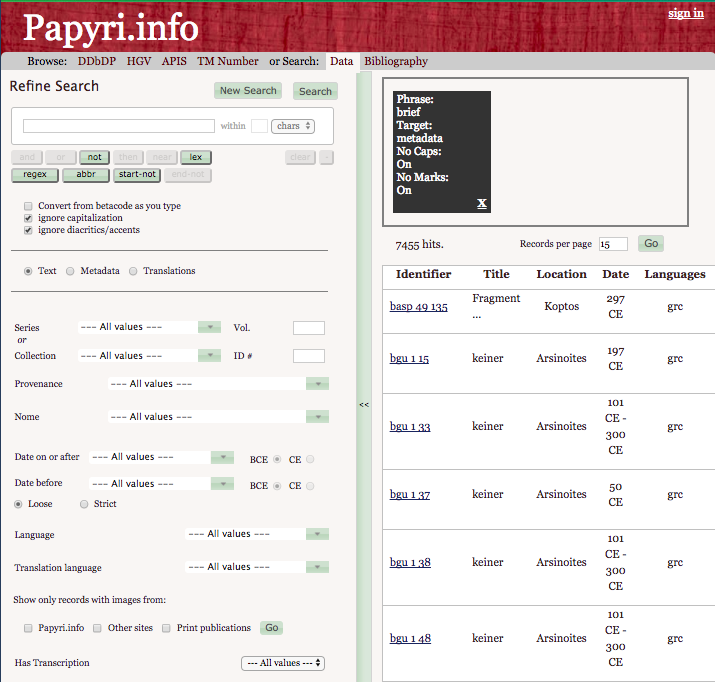

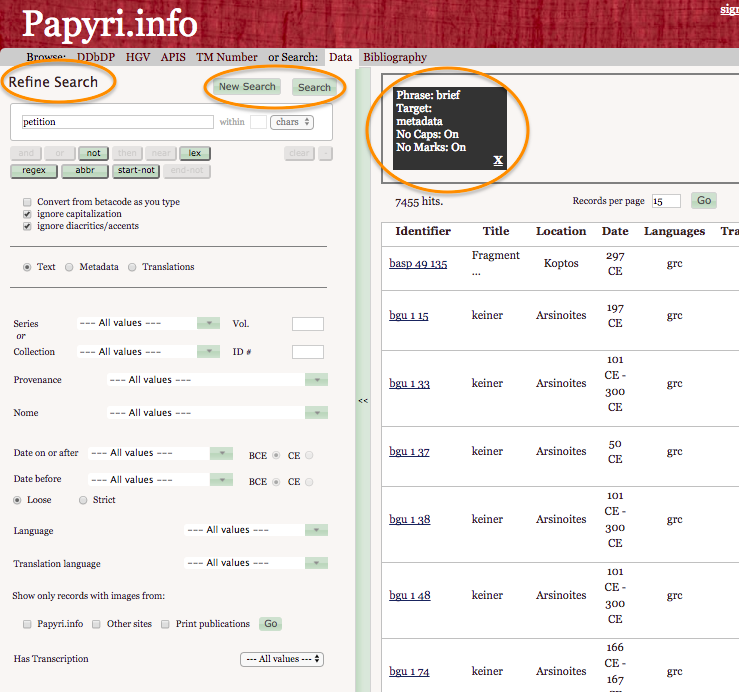

31The user interface is divided into two columns, which contain the search form, on the left-hand side, and detailed directions for its use, on the right-hand side (fig. 21), respectively. A small drawback of the directions’ display is that, if we narrow the browser window even only slightly, they move to the bottom of the page, sometimes becoming completely invisible. We also cannot see the directions after performing a search, as the right column gets occupied by the list of the results (fig. 22). Hence it would be useful to always have a link to the directions, in the result page, too, as one interviewed user highlighted. In fact, she could not recall where the directions were, as they are not available on the result page and she did not notice them on the PN home page, since she was focused on the left part of the screen to enter her data. The link to the search directions could be added to the grey menu bar on top of the page, after the “Bibliography” link, thereby being visible on every page and regardless of the width of the browser window.

32Users can choose to search the texts, the metadata or the translations by selecting the respective buttons. It would be a small improvement to facilitate a new search on the result page of a previous query, rather than on the home page.

33On the result page, one may expect that entering a new word and hitting the “Search” button will perform a new search; the result is, instead, a refined search. Users should, in fact, click on the x-button in the black box on top of the results to remove the previous search value; however, this button is not evident, as was also pointed out by one of the interviewed users. As an alternative, one can perform a new search by clicking on the “New Search” button; users, though, need to remember that they should first click on “New Search”, and only then enter the new value (and finally perform their search by hitting “Search”): if one types the new word first, and then hits “New Search”, as it may happen, this will remove the new value. This aspect could be improved by allowing the “New Search” button to perform a search with the new value, rather than to go back to the PN home page. Moreover, the “Search” button could be renamed “Refine Search” to explain its function more clearly; even though this phrase is already present, on the top left, it would be more evident if it was positioned on the button, where users actually need to click.

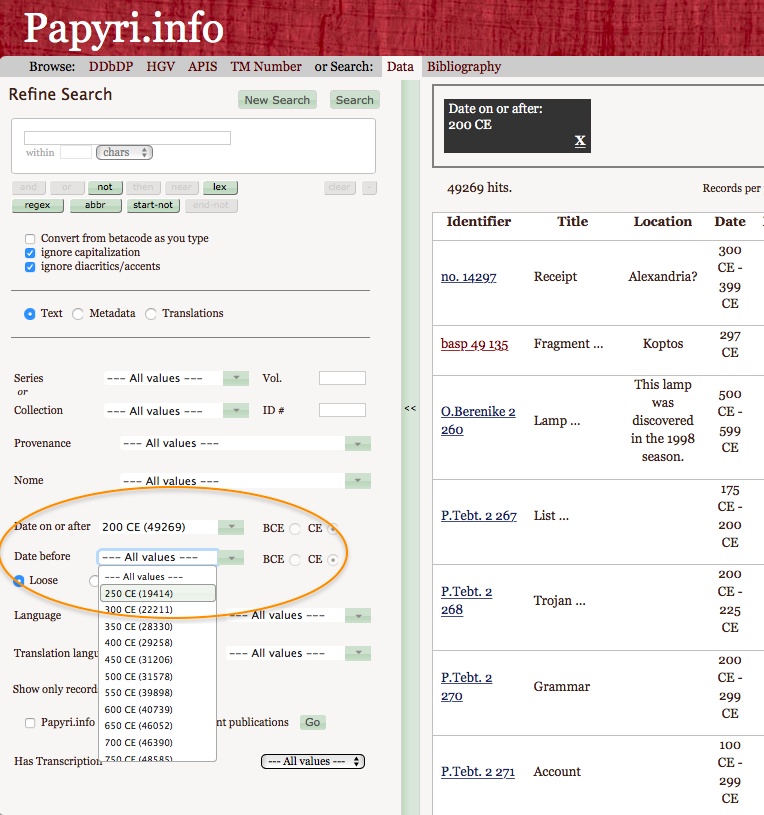

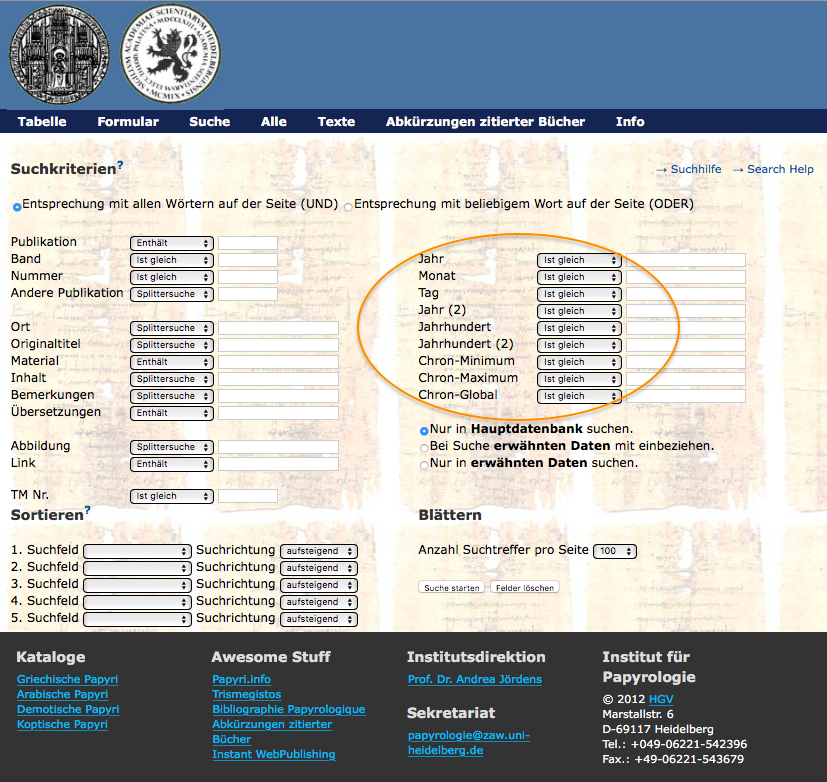

34Other aspects of the PN user interface can be better illustrated by way of a comparison with the interface of the HGV, the Heidelberg database with records of metadata. As we have seen, the PN offers more accurate results than the HGV because it does not contain multiple records for the same papyrus, as the HGV does whenever a dating is uncertain. On the other hand, a reason why one may still wish to utilise the HGV database is that its interface offers more possibilities of search than that of the PN. The HGV allows searching for a date according to a single year, and even a month or a day; moreover, one can search for any range of time (by entering any year into the “ChronMinimum” and “ChronMaximum” fields). Instead, on the PN one can perform a search by date exclusively by selecting a predefined value in the “Date on or after” and/or “Date before” fields, within a fifty-year range. Surprisingly, if one tries searching for a single year among the PN metadata (by entering it in the search field and selecting the “Metadata” option), no result is retrieved, although the help information (in the right-hand pane of the search) states that this search is possible, as one in fact expects.37

35Another frequent kind of search is the one by content type, as scholars need to find documents of the same type (e.g., a petition or a will), to study their features and to verify supplements in lacunous passages. This kind of search is possible in the PN, too, like in the HGV, but it is less clear to find out how this search works. While in the Heidelberg database there is a specific field for the search by kind of content, in the PN this information needs to be searched for in the “Search” field, ticking the “Metadata” option, as it does not have a dedicated field, unlike, for example, “Provenance” or “Date”. In this way, the ability to do this search may not be evident: one of the users I interviewed was not aware of that possibility, even though he had interest in finding documents of a specific type on which his research focuses. Above all, users are not made aware that, because the metadata is imported from the HGV, the term referring to the content type needs to be entered in German (whereas in the HGV search interface this is self-evident as German is the language of all the information throughout the database). In fact, in every PN record the content type of a papyrus is indicated by a term in German, in the “Subjects” field of the HGV section (fig. 25). Because this indication is not reported, one of the users I interviewed, to make sure to find all the documents of a specific type in whatever language they have been published, enters the term of her interest in several languages (English, German, French and Italian), which is however unnecessary.

36It is also true that users look for types of documents not only by means of a metadata search, but also by searching the texts for significant words that are typical of certain documents; they are therefore able to find texts of a certain category with this other method. Two users I interviewed combine this kind of search with the previous one about the metadata: for example, they look up formulas or keywords, like “ἐξαυτῆς” (“at once”), a word typically occurring in summons, in order to retrieve all the texts of this category. Indeed, the HGV warns users that “there is no guarantee of completeness in the case of searching according to content as we did not develop a system of categorisation”38; it would be useful to point out this limitation in the PN search form, as well, in the help information in the right-hand part of the search page (among the information about “Metadata”, in the “More about string-search”), so as to suggest users to use both search methods.

37In conclusion, there are a few circumscribed problems that slightly limit the usability of the search interface, especially for first users, sometimes causing them to spend more time than necessary when performing a new search, looking for typologies of documents, and seeking for texts within a limited time-span.

Conclusion

38The process of integration of the three main databases, accomplished in the Integrating Digital Papyrology project, has allowed the integration of different kinds of data, in different formats: the texts, coming from the Duke Databank and encoded in Beta Code and SGML, were converted into Unicode and EpiDoc TEI; they were integrated with the metadata and the images, on records encoded in FileMaker and exported to XML, from the Heidelberg HGV and the Michigan APIS databases. The merging of texts and metadata was facilitated by the addition, to the texts, of a unique identifier, i.e., the Trismegistos number. A great effort was put into this process, in the Integrating Digital Papyrology project which consisted in three phases and lasted six years, from 2007 to 2012 (Sosin 2010, Baumann et al. 2011). Papyrologists can thus now access their main resources from only one extensive platform. The conversion to EpiDoc, an open markup standard which is a subset of TEI, ensures that Papyri.info has a high degree of compatibility with other projects in the Humanities and a long-term sustainability.

39To summarise the strengths and weaknesses of Papyri.info, we might highlight that the comprehensiveness of the material, the integration of the different databases (both of texts and metadata, and of research tools) and the ability of an integrated search across them explain why this is an indispensable resource for the study of documentary papyri. However, precisely to valorise the collection, that is, to enable users to take advantage of all its features, there should be a better communication about the characteristics of its content and tools, and about the procedure to contribute new data. Other useful additions would be pointing to resources where similar content can be found, as happens for the literary and medical papyri on the Digital Corpus of Literary Papyri, and more accuracy in the documentation relative to the involved institutions and staff.

Notes

1. The launch took place at the XXVI International Congress of Papyrology (Geneva), with a talk by Joshua Sosin (Sosin 2010); this information is reported in the “About” page of Papyri.info, https://web.archive.org/web/20170603015536/http://www.papyri.info/docs/about.

2. This collaborative model of publishing, which also includes an editorial board to ensure the quality of the texts, is illustrated in Baumann 2013, 92-93; Bagnall 2010, 5-6; Sosin 2010.

3. For the physical collections that have been digitised in the APIS database, see the overview of this project outlined in Bagnall-Gagos 2007, in part. 66-67. Roger Bagnall and Traianos Gagos, founders of APIS, soon realised the potential for digitisation to bring to light almost forgotten collections; this led them to digitise not only the papyri of the Michigan and other American collections, but also some unpublished papyri of European institutions (Bagnall-Gagos 2007, 66-67).

4. Gagos 1996, 19-20; Gagos 1997, 155.

5. These figures are drawn from the search form on the PN home page: at the bottom, the drop-down menu of the “Has Transcription” selection criterion shows the values “true (55080)” and “false (31936)”. As one can infer, this indicates the records complete with texts and those which so far exclusively contain metadata.

6. Cf. Evans-Obbink 2010, 1-3, for an overview on the significance of the papyri for the study of the ancient languages. The authors also explain how the research on the language of the papyri is one of the areas that mostly benefits from technological advances. Through the citations of the DDbDP in this volume (found by searching for “DDbDP” in the index) one can find instances of linguistic researches conducted with the aid of this database, now merged into Papyri.info.

7. Sosin 2010; Papyri.info, “The DDbDP”; Integrating Digital Papyrology 3, 10-11, 18-21.

8. J. Cowey and C. Lanz, personal communications.

9. On the decisive contribution of the Packard Foundation and the PHI to the creation of the DDbDP, see the history of this database outlined in Oates 1993, 62-64, 69-71.

10. On the conversion of the texts in Beta Code and SGML into Unicode and EpiDoc XML, see Baumann et al. 2011, esp. “Integrating Digital Papyrology” and “Lessons from the conversion of the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri from legacy formats into EpiDoc TEI XML”; Baumann (2013, 93-100) explains the choice of Git and its functioning; Baumann et al. 2011, esp. “The Papyrological Navigator: Project Integration with RDF”, and Baumann 2013, 100 deal with the use of an RDF triplestore for integrating the source databases.

11. I was provided with the above information on the updating of the HGV and the PN by James Cowey and Carmen Lanz, in personal communications.

12. Joshua Sosin, personal communication.

13. James Cowey, personal communication. The presence of multiple records for one text, in order to represent different possibilities of dating, has also been reported in Hagedorn 1994, 227, and in Bagnall 1998. For example, a search for petitions retrieves 2251 results on the PN and 2285 on the HGV (it is possible to search for the content type by entering a term in German, e.g. “Eingabe” for “petition”, both in the HGV, in the “Inhalt” field, and in the PN selecting the “Metadata” option).

14. This feature has been noted by Reggiani (2017, 74-75).

15. James Cowey, personal communication. The presence of multiple records for one text, in order to represent different possibilities of dating, has also been reported in Hagedorn 1994, 227, and in Bagnall 1998. For example, a search for petitions retrieves 2251 results on the PN and 2285 on the HGV (it is possible to search for the content type by entering a term in German, e.g. “Eingabe” for “petition”, both in the HGV, in the “Inhalt” field, and in the PN selecting the “Metadata” option).

16. We find this information on the Bibliographie Papyrologique home page: ‘Une version électronique simplifiée de la «BP rétrospective» (provisoirement arrêtée en 2012) est également accessible via la plate-forme papyri.info’. This problem is pointed out in Reggiani (2017, 20-21).

17. Cf. Reggiani 2017, 20-22 for this discussion on the advantages of the integration between the PN and the BP.

18. https://web.archive.org/web/20170603015536/http://www.papyri.info/docs/about, see below, fig. 3.

19. Reggiani (2017) has in fact used the information available on the Digital Papyrology blog to show the modifications added to Papyri.info over the years; see, e.g., Reggiani 2017, 236, n. 119.

20. A user I interviewed proved not to be aware of the scope of the collection, as she remarked that she cannot find, on the PN, the literary papyri she needed; she had been attending a module of Papyrology a few years ago, but either was not given this indication or was not able to recollect it as she had then not carried out papyrological research for a few years.

21. Cf. the DCLP home page: “DCLP offers information about and transcriptions of Greek and Latin literary and subliterary papyri”. On the addition of literary and medical papyri to this database, see Reggiani 2017, 253, 274-275.

22. On the development of this project of the University of Parma, and on a discussion of the issues involved in the digitisation of texts with different features from the documentary ones, see Reggiani 2016 and Reggiani 2017, 251-254, 274-275.

23. Cf. Reggiani 2017, 275: “At the time, digitizations took place in the Papyrological Editor, in a special community called ‘ParmaMed’, which avoided the phase of submitting the edited texts to the Papyri.info board; when the DCLP challenge started, the Parma medical project became one of the earliest partners to contribute content”.

24. Oates 1993, 64-66; Willis 1984, 167-169.

25. The sixteen users I have interviewed to date include PhD students and early career researchers of different European universities. Interviews and other data will be analysed in my PhD dissertation with the title The role of Digital Humanities in Papyrology: practices and user needs in papyrological research, at the Institute of Classical Studies, London. This analysis aims to gain insight into the scholarly use of Digital Classics methods and tools, in particular by papyrologists and other classicists who need to consult papyrological resources.

26. EpiDoc guidelines and material are available at http://epidoc.sf.net (accessed 11 January 2018). A list of projects that use the EpiDoc standards is available at The Digital Classicist Wiki, “Category:EpiDoc”, https://web.archive.org/web/20170930144706/https://wiki.digitalclassicist.org/C….

27. Cf. Integrating Digital Papyrology 3; Sosin 2010.

28. For more details on the history of EpiDoc, I refer to Bodard 2010, 101-104, and Cayless et al. 2009, 1-2.

29. Creative Commons, “Attribution 3.0”, https://web.archive.org/web/20170930110422/https://creativecommons.org/licenses…. As well as the XML files of the texts, also the code of its core components is open to reuse, as it is freely available online, stored in Git (Baumann 2013).

30. The information on the GitHub repository, where the complete data of Papyri.info can be accessed, is only reported, as far as I am aware, in the bibliography where the GitHub repository is mentioned (Baumann 2013, 93-100), and on The Digital Classicist. The Digital Classicist Wiki. “Greek and Latin texts in digital form”. https://wiki.digitalclassicist.org/Greek_and_Latin_texts_in_digital_form#Texts_…. Accessed 2 February 2018.

31. Sematia. University of Helsinki. https://sematia.hum.helsinki.fi/docs/. Accessed 5 October 2017. This project and the issues of linguistic annotation of fragmentary papyrus texts are discussed in Reggiani 2017, 182-184.

32. KU Leuven, Research Portal, “Variety and change in the Ancient Greek papyri: a corpus-linguistic study of the use of tense, aspect and modality in the Greek complementation system” by A. Keersmaeker, https://www.kuleuven.be/onderzoek/portaal/#/projecten/3H160543 (accessed 10 October 2017).

33. One of the interviewees mentioned the fact that there are no morpho-syntactic annotations in the texts in the PN, which therefore cannot be queried in this way, for example to search for all the infinitives. By the same token, Clarysse (2010, 44) remarks the absence of syntactical annotation, which would permit to search for different kinds of clauses.

34. The procedure for extracting person names from the texts of the DDbDP is described in Depauw-van Beek 2009, 33-37.

35. TM Words (https://web.archive.org/web/20180313155651/https://www.trismegistos.org/words/i…), unlike the others TM databases, is not indicated on the TM platform homepage, maybe because it is still in its beta phase. It is anyway known to papyrologists as it was announced by Mark Depauw, the TM project director, on the Papy-list, the papyrological discussion list, on 9 January 2018.

36. Papyri.info, “Text Leiden+ Documentation”, https://web.archive.org/web/20171010170456/http://papyri.info/docs/leiden_plus.

37. Cf. the following passage in the “More about string-search” section, about the metadata search: “Metadata: Searches the metadata associated with the document – for example, the identification number, location, and dating of the document”.

38. HGV, “Search Tips and other Information”, https://web.archive.org/web/20171004170724/http://aquila.zaw.uni-heidelberg.de/….

References

- APIS – Advanced Papyrological Information System, University of Michigan Library, https://web.archive.org/web/20160810083015/http://www.lib.umich.edu:80/papyrolo….

- Arethusa. https://web.archive.org/web/20171009155602/http://www.perseids.org/tools/arethu….

- Bagnall, R. S. 1998. “Review of Heidelberger Gesamtverzeichnis der griechischen Papyrusurkunden Ägyptens”. Bryn Mawr Electronic Resources Review. http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/bmerr/1998/BagnaHeideAug.html. Accessed 24 October 2018.

- Bagnall, R. 2010. “Integrating digital papyrology”. In Online humanities scholarship: the shape of things to come, edited by F. Moody & B. Allen. New York: Mellon Foundation. http://hdl.handle.net/2451/29592. Accessed 30 September 2017.

- Bagnall R. S. and T. Gagos. 2007. “The Advanced Papyrological Information System: Past, Present, and Future.” In Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Papyrology, Helsinki 2004, edited by J. Frösén, T. Purola, and E. Salmenkivi, vol. 1, 59-74. Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica.

- Baumann, R. 2013. “The Son of Suda On-Line”. In The Digital Classicist 2013 ( = BICS Supplement 122), edited by S. Dunn and S. Mahony, 91-106. London: Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. https://web.archive.org/web/20171025174938/https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspac….

- Baumann, R., G. Bodard, H. Cayless, J. Sosin, and R. Viglianti. 2011. “Panel: Integrating Digital Papyrology”, in Digital Humanities 2011: June 19-22, Conference of the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations, hosted by the Stanford University Library. https://web.archive.org/web/20170710154928/http://dh2011abstracts.stanford.edu/….

- Berichtigungsliste der griechischen Papyrusurkunden aus Ägypten, voll. 1-13. 1922-2017.

- Bibliographie Papyrologique. Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Centre de Papyrologie et d’Épigraphie greque de l’Université libre de Bruxelles. http://www.aere-egke.be/BP.htm. Accessed 25 September 2017.

- Bodard G. 2010. “EpiDoc: Epigraphic Documents in XML for Publication and Interchange”. In Feraudi-Gruénais, F. 2010. Latin on stone: Epigraphic Research and Electronic Archives. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 101-118. https://web.archive.org/web/20180111113342/http://www.stoa.org/wordpress/wp-con….

- Cayless H., C. Roueché, T. Elliott, and G. Bodard. 2009. “Epigraphy in 2017”. Digital Humanities Quarterly 3.1. https://web.archive.org/web/20170624164625/http://www.digitalhumanities.org:80/….

- Clarysse, W. 2010. “Linguistic Diversity in the Archive of the Engineers Kleon and Theodoros”. In Evans-Obbink 2010, 35-50.

- Digital Corpus of Literary Papyri (DCLP). University of Heidelberg. https://web.archive.org/web/20171024181128/http://litpap.info.

- Digital Papyrology blog. https://web.archive.org/web/20170927110954/http://digitalpapyrology.blogspot.co….

- Depauw M. and B. Van Beek. 2009. “People in Greek Documentary Papyri. First Results of a Research Project”. JJP 39, 31-47.

- EpiDoc: Epigraphic Documents in TEI XML. Elliott T., Bodard G., Cayless H., et al. (2006-2016), Online material, available: http://epidoc.sf.net. Accessed 30 September 2017.

- Evans, T.V. and D.D. Obbink. 2010. The language of the papyri. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gagos, T. 1996. “Scanning the Past: A Modern Approach to Ancient Culture.” Library Hi Tech, 14 (1): 11-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb047974. Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Gagos, T. 1997. “Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS): The Michigan Experience.” LLC 12 (3): 155-157. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/12.3.155. Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Hagedorn D. 1994. “Gesamtverzeichnis der griechischen Papyrusurkunden Ägyptens” In Datenbanken in der Alten Geschichte ( = Computer und Antike 2), edited by M. Fell, C. Schäfer, L. Wierschowski, 226-231. St. Katharinen.

- HGV – Heidelberger Gesamtverzeichnis der griechischen Papyruskunden Ägyptens, Institut für Papyrologie. Universität Heidelberg. https://web.archive.org/web/20170713104205/http://aquila.zaw.uni-heidelberg.de/….

- Oates J. F. 1993. “The Duke Data Bank of Documentary Papyri”. In Accessing Antiquity:

- Papyri.info. https://web.archive.org/web/20170925124125/http://papyri.info.

- Reggiani N. 2016. “The Corpus of Greek Medical Papyri and Digital Papyrology: new perspectives from an ongoing project”. In Altertumswissenschaften in a Digital Age: Egyptology, Papyrology and beyond. Proceedings of a conference and workshop in Leipzig, November 4-6, 2015, edited by M. Berti and Naether. Leipzig. https://web.archive.org/web/20171024182110/http://www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/….

- Reggiani N. 2017. Digital Papyrology, vol. 1, Methods, Tools and Trends. Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter. https://www.degruyter.com/viewbooktoc/product/486978. Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Sematia. University of Helsinki. https://sematia.hum.helsinki.fi/docs/. Accessed 5 October 2017.

- Sosin J., 26 October 2010. “Digital Papyrology”. Blog post on The Stoa Consortium. https://web.archive.org/web/20170408110552/http://www.stoa.org/archives/1263.

- TEI: Text Encoding Initiative. https://web.archive.org/web/20170711100834/http://www.tei-c.org/index.xml.

- The Digital Classicist. The Digital Classicist Wiki. https://web.archive.org/web/20170715110130/http://wiki.digitalclassicist.org/Ma….

- Trismegistos (TM). KU Leuven. https://web.archive.org/web/20170701160733/http://www.trismegistos.org/index.ht….

- Willis W. H. 1984. “The Duke Data Bank of Documentary Papyri”, in Atti del XVII Congresso Internazionale di Papirologia, Napoli 1983, vol. 1, 167-173. Napoli: Centro internazionale per lo studio dei papiri ercolanesi.

- Willis W. H. 1988. “The Duke Data Bank of Documentary Papyri”. In Proceedings of the XVIII International Congress of Papyrology, Athens 1986, edited by B. Mandilaras, vol. 2, 15-20. Athens: Greek Papyrological Society.

- Willis W. H. 1992. “The new mode of access to the Duke Data Bank of Documentary Papyri”. In Proceedings of the XIX International Congress of Papyrology, Cairo 1989, edited by A. H. S. El-Mosalamy, vol. 1, 125-131. Cairo: Ain Shams University.

- Willis W. H. 1994. “The New Compact Disk of Documentary Papyri”. In Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Papyrology, Copenhagen 1992, edited by A. Bülow Jacobsen, 628-631. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, University of Copenhagen.